“If I can’t hope, nothing’s ever gonna change“ – Hope by the Cable Ties

“Coronavirus brings out the worst (and best) in us” – TU P

Here are two articles Can you spread Covid-19 if you get the vaccine? and COVID vaccines: calling the shots.

The former is written from a medical perspective. Unfortunately the paper doesn’t say anything … poses a crucial question about vaccines effect on the spread of Covid that many have been wondering about for some time and then fails to answer it.

The latter is about big drug companies reluctance to produce vaccines. And how they changed course in 2020. The article is by British Marxist economist Michael Roberts about how we need public ownership of vaccine development!

Please note I would be careful about drug companies claims of efficacy (= the ability to produce a desired or intended result) of the Covid vaccines. There is insufficient data to support what are, at best, press releases by drug companies and compliant politicians. Here is the quote from the article COVID vaccines: calling the shots.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine against COVID-19 was reported to have over 90% efficacy. Moderna reported that its vaccine reduced the risk of COVID-19 infection by 94.5%.

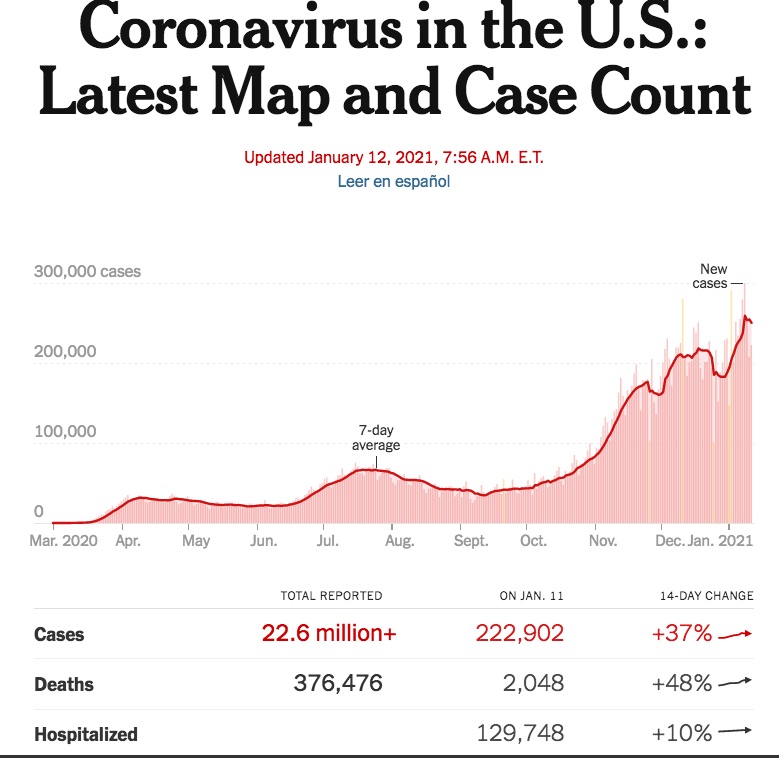

The article asks why big pharmaceutical companies are suddenly interested in creating vaccines, the US statistics in the graph below give a clue.

– Ian Curr, 13 Jan 2021.

Chilling US Covid Stats as at 12 Jan 2021

__oOo__

COVID vaccines: calling the shots

Before the COVID-19 pandemic engulfed the world, the big pharmaceutical companies did little investment in vaccines for global diseases and viruses. It was just not profitable. Of the 18 largest US pharmaceutical companies, 15 had totally abandoned the field. Heart medicines, addictive tranquilizers and treatments for male impotence were profit leaders, not defences against hospital infections, emergent diseases and traditional tropical killers. A universal vaccine for influenza—that is to say, a vaccine that targets the immutable parts of the virus’s surface proteins—has been a possibility for decades, but never deemed profitable enough to be a priority. So, every year, we get vaccines that are only 50% efficient.

But the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the attitude of big pharma. Now there are billions to be made in selling effective vaccines to governments and health systems. And in double-quick time, a batch of apparently effective vaccines has emerged with every prospect of them being available for people within the next three to six months – a record result.

There should be authorisation of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines by year-end in the EU and the UK, with the deployment of an initial 10-20 million doses each (5-10 million treatments) underway through the turn of the year. Widespread vaccination from COVID-19 beyond high-risk groups is likely to be underway across Europe by the spring, with a sufficiently large share of European populations vaccinated by the end of the summer.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine against COVID-19 was reported to have over 90% efficacy. Moderna reported that its vaccine reduced the risk of COVID-19 infection by 94.5%. Among other leading vaccine developers, AstraZeneca is expected to release Phase III trial results by Christmas, with a number of others currently also conducting late-stage trials. By year-end, the EU and the UK should have enough doses to treat around 5 million people each (with a single treatment involving two doses). And there are others: Gamaleya, Novavax, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi-GSK; as well as the Sputnik vaccine from Russia and China’s own.

How was this possible so quickly? Well, it was not due to big pharma coming up with the scientific research solutions. It was down to some dedicated scientists working in universities and government institutes to come up with the vaccine formulas. And that was made possible because the Chinese government quickly provided the necessary DNA sequences to analyse the virus. In sum, it was government money and public funds that delivered the medical solution.

Basic research for US vaccines is done by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Defense Department and federally funded academic laboratories. The vaccines made by Pfizer and Moderna rely heavily on two fundamental discoveries that emerged from federally funded research: the viral protein designed by the NIH; and the concept of RNA modification first developed at the University of Pennsylvania. In fact, Moderna’s founders in 2010 named the company after this concept: “Modified” + “RNA” = Moderna.

So Moderna’s vaccine has not come out of nowhere. Moderna had been working on mRNA vaccines for years with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), a part of the NIH. The agreement consisted of some level of funding from Moderna to the NIH, along with a roadmap for NIAID and Moderna investigators to collaborate on basic research into mRNA vaccines and eventually development of such a vaccine.

The US government has poured an additional $10.5 billion into various vaccine companies since the pandemic began to accelerate the delivery of their products. The Moderna vaccine emerged directly out of a partnership between Moderna and the NIH laboratory.

The US government—and two agencies in particular, the NIH and Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA)—has invested, heavily, in the vaccine’s development. BARDA is an arm of the Department of Health and Human Services formed in 2006 in response to—wait for it—SARS-CoV-1 (and other health threats). It provides direct investment in technologies to firms, but also engages in public-private partnerships (PPPs) and coordinates between agencies. A specific part of BARDA’s mission is taking technologies through the “valley of death” between creation and commercialization.

The German government ploughed funds into BioNTech to the tune of €375 million, with another €252 million has been made to support development by CureVac. Germany also raised its contribution to the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) by €140 million and plans to provide an additional €90 million next year. CEPI was launched in Davos, Switzerland, in 2017 as an innovative global partnership between public, private, philanthropic and civil society organisations to develop vaccines to counter epidemics, and Germany pledged an annual €10 million over a four-year period to support the initiative. CureVac is one of nine institutes and companies commissioned by CEPI to conduct research into a COVID-19 vaccine. One of its shareholders is the government-owned Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW) bank.

But it is big pharma that develops the vaccine from the scientific work of public institutes. They call the shots. The drugs companies do the global clinical trials, then produce and market the result. Then they sell the vaccines to governments at huge profits. This is the way things were done before the pandemic – and now. In the US, in the 10-year period between 1988 and 1997, public-sector expenditures for vaccine purchases doubled from $100 to $200 per child through age 6. The cumulative public-sector cost doubled again in less than 5 years between 1997 and 2001, from $200 to almost $400 per child.

Very little is still known about the terms of the COVID vaccine contracts that EU governments have signed with pharma groups including AstraZeneca, Pfizer-BioNTech, Sanofi-GlaxoSmithKline and CureVac. But once the secrecy is peeled away, what we will see is a massive privatisation of billions of dollars of government funds. It is reckoned that the AstraZeneca has sold its jab to governments at about $3 to $4 a dose, while the Johnson & Johnson shot and the vaccine jointly developed by Sanofi and GSK were priced at about $10 a dose. AstraZeneca has promised not to profit from its jab during the pandemic, but that applies only until July 2021. After that, they can cash in. US biotech Moderna is going to charge $37 a dose, or $50 to $60 for the two-shot course.

Coronavirus vaccines are likely to be worth billions to the drug industry if they prove safe and effective. As many as 14 billion vaccines would be required to immunize everyone in the world against COVID-19. If, as many scientists anticipate, vaccine-produced immunity wanes, billions more doses could be sold as booster shots in years to come. And the technology and production laboratories seeded with the help of all this government largesse could give rise to other profitable vaccines and drugs.

So while much of the pioneering work on mRNA vaccines was done with government money, the privately owned drugmakers will walk away with big profits, while governments pay for vaccines they helped to fund the development of in the first place!

The lesson of the coronavirus vaccine response is that a few billion dollars a year spent on additional basic research could prevent a thousand times as much loss in death, illness and economic destruction. At a news conference US health adviser, Anthony Fauci, highlighted the spike protein work. “We shouldn’t underestimate the value of basic biology research,” Fauci said. Exactly. But as many authors, such as Mariana Mazzacuto have shown, state funding and research has been vital to development of such products.

What better lesson can we learn from the COVID vaccine experience than that the multi-national pharma companies should be publicly owned so that research and development can be directed to meet the health and medical needs of people not the profits of these companies. And moreover, then the necessary vaccines can get to the billions in the poorest countries and circumstances rather than to just those countries and people who can afford to pay the prices set by these companies.

“This is the people’s vaccine,” said corporate critic Peter Maybarduk, director of Public Citizen’s Access to Medicines program. “Federal scientists helped invent it and taxpayers are funding its development. … It should belong to humanity.”

Michael Roberts

__oOo__

Here’s another article from a medical perspective.

Unfortunately the paper doesn’t say anything … poses a crucial question that many have been wondering about for some time and then fails to answer it. But then there isn’t an answer until it is tried.

I know enough about the immune response to say that the vaccines developed so far are no great theoretical advance. All they do is stimulate macrophages (cells that eat invasive germs and cells infected with viruses like Covid. The RNA vaccine put out by Pfizer-BioNTech is a little different but not much. Plus it is unstable over time unless stored at in an ultra cold freezer which may represent a logistical problem in, say, remote parts of Africa.

Basically the antigen (the vaccine) stimulates a response from lymph nodes that will attack the SARS-CoV-2 virus ( Covid 19 ) virus when it enters the mucosa (the lining of the airwaves i.e. nose, mouth, pharynx lungs).

The problem is you are already infected when this happens so you may infect others in confined spaces i.e. by cough over them. The paper below explains why we don’t know the answer to the question: Can you spread Covid-19 if you get the vaccine?

—————

Ian Curr

Editor WBT

(I spent a year working in a immunological lab in 1968 and have a B.Sc. from UQ in Biological Sciences)

15 Jan 2021

__oOo__

Can you spread Covid-19 if you get the vaccine?

We know that the vaccines now available across the world will protect their recipients from getting sick with Covid-19. But while each vaccine authorized for public use can prevent well over 50% of cases (in Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna‘s case, more than 90%), what we don’t know is whether they’ll also curb transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

That question is answerable, though—and understanding vaccines’ effect on transmission will help determine when things can go back to whatever our new normal looks like.

The reason we don’t know if the vaccine can prevent transmission is twofold. One reason is practical. The first order of business for vaccines is preventing exposed individuals from getting sick, so that’s what the clinical trials for Covid-19 shots were designed to determine. We simply don’t have public health data to answer the question of transmission yet.

The second reason is immunological. From a scientific perspective, there are a lot of complex questions about how the vaccine generates antibodies in the body that haven’t yet been studied. Scientists are still eager to explore these immunological rabbit holes, but it could take years to reach the bottom of them.

Acting the part

Vaccines work by tricking the immune system into making antibodies before an infection comes along. Antibodies can then attack the actual virus when it enters our systems before they have a chance to replicate enough to launch a full-blown infection. But while vaccines could win an Oscar for their infectious acting job, they can’t get the body to produce antibodies exactly the same way as the real deal.

From what we know so far, Covid-19 vaccines cause the body to produce a class of antibodies called immunoglobulin G, or IgG antibodies, explains Matthew Woodruff, an immunologist at Emory University. IgG antibodies are thugs: They react swiftly to all kinds of foreign entities. They make up the majority of our antibodies, and are confined to the parts of our body that don’t have contact with the outside world, like our muscles and blood.

But to prevent Covid-19 transmission, another type of antibodies could be the more important player. The immune system that patrols your outward-facing mucosal surfaces—spaces like the nose, the throat, the lungs, and digestive tract—relies on immunoglobulin A, or IgA antibodies. And we don’t yet know how well existing vaccines incite IgA antibodies.

“Mucosal immunology is ridiculously complicated,” says Woodruff. “Rather than thinking of immune system as a way to fight off bad actors, it’s really a way for your internal environment to maintain some sort of homeostatic existence with a really dynamic outside world,” as you breathe, eat, drink, and touch your face.

People who get sick and recover from Covid-19 produce a ton of these more-specialized IgA antibodies. Because IgA antibodies occupy the same respiratory tract surfaces involved in transmitting SARS-CoV-2, we could reasonably expect that people who recover from Covid-19 aren’t spreading the virus any more. (Granted, this may also depend on how much of the virus that person was exposed to.)

But we don’t know if people who have IgG antibodies from the vaccine are stopping the virus in our respiratory tracts in the same way. And even if we did, scientists still don’t know how much of the SARS-CoV-2 virus it takes to cause a new infection. So even if we understood how well a vaccine worked to prevent a virus from replicating along the upper respiratory tract, it’d be extremely difficult to tell if that would mean a person couldn’t transmit the disease.

Making it real

Because of all that complication, it’s unlikely that immunological research alone will reveal how well vaccines can prevent Covid-19 transmission—at least, not for years. But there’s another way to tell if a vaccine can stop a person from transmitting a virus to others: community spread.

As more and more people get both doses of a Covid-19 vaccine (and wait a full two weeks after their second dose for maximum immunity to kick in), public health officials can see how fast case counts fall. It may not be a perfect indicator of whether we’re stopping the virus in its tracks—there are many other variables that can slow transmission, including lockdown measures—but for practical purposes, it’ll be good enough to help make public health decisions.

Plus, even though the data we have from clinical trials isn’t perfect, it’s a pretty good indicator that the vaccine at least stops some viral replication. “I can’t imagine how the vaccine would prevent symptomatic infection at the efficacies that [companies] reported and have no impact on transmission,” Woodruff says.

Each of the vaccines granted emergency use in western countries—Moderna, Pfizer-BioNTech, and AstraZeneca—have all shown high efficacy in phase 3 clinical trials. (The Sinopharm and Sinovac vaccines from China and the Bharat Biotech vaccine in India have also been shown to be effective at preventing Covid-19, but aren’t widely approved for use yet.)

Frustratingly, it’s just going to take more time to see if people who got the vaccine are involved in future transmission events. That’s why it’s vital that even after receiving both doses of the Covid-19 vaccine, all individuals wear masks, practice physical distancing, and wash their hands when around those who haven’t been vaccinated—just in case.