Everybody knows that the dice are loaded

Everybody rolls with their fingers crossed

Everybody knows that the war is over

Everybody knows the good guys lost

Everybody knows the fight was fixed

The poor stay poor, the rich get rich

Thats how it goes

Everybody knows

— Leonard Cohen

Publisher’s Note

Published below are a series of articles about the current crisis in capitalism by Humphrey McQueen ‘to remind people of what used to be obvious’.

It is important that socialists everywhere look to renewal in the class struggle, being mindful of our faults and to take responsibility for our failings.

Hopefully this series by Humphrey McQueen will assist us in understanding what is happening now so that we can face the future with more confidence.

The articles (in order) are in the Table of Contents. More recent chapters have been linked to the text, the older ones can be read below the Table of Contents.

A print friendly version is updated from time to time and is also provided below. The more political ones are in bold, the more economic ones are in plain — each article may be read alone, understanding does not require knowledge of the article before it they are merely arranged in the order that Humphrey McQueen sent them to Workers BushTelegraph.

Ian Curr

Editor

Workers BushTelegraph

February2009

For a PDF version of this series click here on-the-crisis

Table of Contents

The following articles (missiles) can be found by clicking on the links below:

- We Built This Country — building trades strikes of 1896-97

- ‘Capital history’

- Spirit of Eureka

- Michael Lebowitz: ‘A dialectically materialist critic of political economy’

- Marx and the Crisis

- Priorities

- Darwin, Lincoln and the survival of the slave-masters

- Crisis! What crisis?

- Never mind the quantity – feel the thinness

- ‘Fictitious capital’

You can find the following ‘missiles’ below:

- Going to extremes

- How bad can get it?

- Swindle Inc?

- The Very Right-wing Rev. Rudd

- Pensions

- Mass Murdoch

- Reformism

- Capitalising the banks

- Fascism

- Revolution: not a dinner party (23 October)

- China: statistical inflation Back to the plan?

- Greed

- O, to be a dinosaur

- If she blows?

- “19 October 1987”

- Not the 1930s (9 October)

- A fiction on fictional capital

- Globalisation

- The Housing Question

- The market for futures

- McValue

- How to lose a trillion

- Don’t pick on bankers

- Not socialism

- Exploitation leads to over-consumption

*******************

Going to extremes

With politicians bleating against “extreme” capitalism, activists need to be clear about our own extremism. Taking a leaf from Equality by the English Christian socialist, R. H. Tawney (1880-1962), here are three ways to be extreme.

First, we need to be extreme in our efforts to understand the dynamics causing the crisis in the accumulation of capital. In particular, we need to get beyond the media pap about a “financial” crisis. We have to recognise that the banking and stock-market upheavals are expressing the il-logic of over-production. The crisis began in the physical economy and is now looping back to intensify those disruptions.

Armed with that understanding, we can become extreme in working out policies to resist any shifting of the costs of the looming catastrophe onto working people. For instance, we need to learn how to tie our understanding of housing finance to tactics for preventing evictions within a strategy to protect the environment.

We can interpret the world only by changing it, and change it effectively only by interpreting it profoundly.

Secondly, we need to be extreme in our preparedness to keep quiet until we have made progress on each element in the previous extreme. Let’s leave it to the politicians to behave like kitchen tidies, their mouths flying open to reveal garbage whenever a journalist steps on their pedals.

No one can know exactly what is happening with the world economy. Still less can we predict where the next eruption will be. No one knows in detail how best to respond to promote the needs of working people. Within the laws of capital accumulation, new things continue to happen. We have to be extreme is keeping up with those developments.

As always, we have to listen and learn. Organising is education for the activist as much as for the masses. The educator must be re-educated.

Thirdly, we must become extreme in our determination to apply the lessons learned from the two other “extremes”. We have to be rigorous in our analysis, ready to jettison early approximations whenever evidence and concepts sharpen our understanding.

In terms of fighting back, the implosion of global capital is no time for rhetorical bluster, of sounding more “left” than everybody else. A huge amount of rebuilding has to be done, organisationally in workplaces and in communities. Many of the insights into exploitation that were taken for granted twenty years ago have to be re-established as common sense.

For each extreme, we could well revive the pledge at Eureka: “We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other and fight to defend our rights and liberties.” In the short term, we need to be extreme in our understanding and application of “truly”.

by Humphrey McQueen

Swindle Inc? (15 December 2008)

With the exposure of the $US50bn scam by NASDAQ chairman Bernie Madoff, another joint has fallen off the walking corpse that is real existing capitalism. This latest blow to confidence is astounding for its simplicity. Madoff paid dividends out of new investments. He could do so because of irrational confidence in his kind.

Faith in the goodness of stock-traders persists. That scourge of corporate boards, Stephen Mayne, assured investors that there isn’t another Madoff out there. Isn’t that what Mayne would have said about Madoff before his arrest? Its more likely that there’s little but Madoffs out there. The more of them who are exposed, the more their edifice trembles, and the more desperate they become to find a Greater Fool to sell out to.

To understand why Madoff is no rotten apple in a spotless barrel, we have to recognise the distinction between the exploitation of workers as the essence of capitalism and the swindling of everybody as an inevitable consequence of that exploitation.

In theory, capitalists need never swindle their wage-slaves. The owners of productive property can exploit their workers if they pay them the full cost of the commodity that they bring to market, that is, their capacity to add value, (labour-power). By disciplining the workers, the owners can get them to produce other commodities of greater value than he price of their labour-power. The difference is known as surplus value.

Viewed in one way, this exchange is fair. The workers get the costs of reproducing themselves for sale. From another perspective, this situation proves why there can never be a fair day’s pay. The capitalists take the surplus value although they do not contribute to its production. (For another account of this fact of working life, see the item headed “The Great Money-Trick” on this site.)

The surplus value is of no use to capitalists unless they can sell the commodities in which it is embodied. But to sell is to incur all manner of expenses from the wholesaler, the retailer, the banker, the marketeer, the accountant, the lawyer – not to mention the candlestick-maker. Each of these firms has to meet its expenses and then some. All those costs have to be taken from the surplus value. Even if all the intermediaries were honourable men, their fees might leave next-to-nothing for the original capitalist.

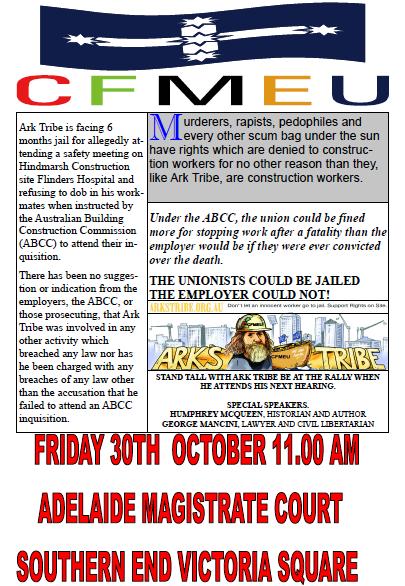

That gentleperson is tempted to overcome that problem by swindling his employees out of some of the wages needed to meet the full costs of their reproducing their labour power. Building contractors do this every hour of every day; Gillard keeps her attack dog in the ABCC to protect such thieves.

But the struggle between classes is not the only area where the tussle for a share of surplus value results in swindling. Capitalists fight their agents over he size of their returns. All parties soon learn that if they don’t grab more than they are entitled to, they won’t end up with enough to pay their bills. Hence, they pad their fees. Lawyers, for instance, charge for quarter-hours they did not work.

The competition for a portion of the results of the exploiting of wage-slaves generates a thousand-and-one schemes. Out of this brew comes an outlook which encourages ever wilder scams from people like Madoff who make no contribution to the realisation of the surplus value. Instead, they offer to increase the horde of money that has resulted from that cycle of investment, production and sale. “I can make you money out of money” is their catch-cry. “Don’t put yourself to all that trouble of disciplining workers and keeping an eye on your friends as they cheat you. Trust me with your cash.”

And they did, to the tune of $US50bn.

Exploitation of wage-slaves need not involve swindles but it cannot be made profitable without some. How unfair that the beneficiaries need not be the exploiter of labour-power. So the money goes round.

The Very Right-wing Rev. Rudd

As part of his PR campaign, K. Rudd proclaimed that he had never been any kind of socialist. Instead, while playing Judas to his leader, he paraded his species of Christianity in an article for Manne Monthly. Rudd extolled the Lutheran pastor, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, whose resistance to Hitler led to his execution in 1945. It is easy to attach yourself to Bonhoeffer when you know you are never going to be put to the tests that he faced. How much easier is it to say, “I oppose Hitler” when you dare not abolish the police-state powers of the Australian Building and Construction Commission.

On the contrary, in 2007, Rudd initiated the expulsion from the ALP of the assistant-secretary of the WA Construction Division, Joe McDonald, because he had called a boss a “fucking thieving parasite dog”. Instead of waiting for the result of an internal Party investigation, Rudd buckled to a Liberal Party internet campaign by sealing McDonald’s expulsion the day after a court had acquitted him of trespass. Joe’s hanging offence had been to assure reporters that, unlike that “burnt-out dictator” John Howard, “I’ll be back” to organise against “getting robbed by unscrupulous bosses.” Rudd found these words “incendiary”, with no place in “a more modern industrial relations system.” Rudd thus put his electoral prospects above the due process that Bonhoeffer had given his life to defend.

The radical poet Victor Daley exposed the speciousness of Rudd’s moralising style in this swipe at the pontificating of the Sydney Morning Herald:

Write boldly, cut and thrust,

‘Gainst wrong in some unseen land;

Denounce the Blubber Trust

That paralyses Greenland …

Be hard on Ancient Rome –

Things dead, or at a distance,

Are safe – but take at home

The line of least resistance.

What has Rudd ever done to show that faith without works is dead? Did he ever join a non-violent protest? Has he put himself in the way of getting arrested in support of a just cause? Even Peter Beattie (former Qld Premier) got nicked during one of the Brisbane Street Marches. Rudd belongs to the would-to-God Brigade: “Would-to-God that I had been born in Germany in 1900, for then I too could have been a martyr.”

Rudd is not the only “tinkling cymbal” in the ministry. Fellow believer Peter Garrett is questing for a principle he cannot betray. A third Christian, Greg Combet, began his campaign against WorkChoices by promising to go to prison. Well, we can’t say he hasn’t ended up among criminal types.

Twas not always thus. For sixty years, Equality, by Christian socialist R. H. Tawney, was the bible of British Labour. Then came the Vicar of Blair. Tawney’s Christianity was as rooted in his commitment to social equality as it was grounded in his character. When the Labour Party offered him a peerage, he replied: “What have I ever done to harm the Labor Party?” Seventy years on, the answer to that question would be to have promoted social equality. Tawney’s name would never be considered for preferment. Instead, he too would be liable to expulsion for his “incendiary” advocacy of social equality, which has no place in “a more modern industrial relations system.”

Thesis Eleven

Clichés clog brains. Around the Left, none will do more mischief in meeting the challenge from the crisis in capital accumulation than two lines from Marx’s so-called “Theses on Feuerbach”: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.”

Parroted by people who should know better, this aphorism is twisted into an un-dialectical choice between “interpret” and “change”.

How can we know which change to effect unless we interpret? Change for its own sake leaves fascism as desirable as socialism. Secondly, how do we work out how to effect a desirable change without interpreting?

Marx’s answer was unequivocal. When he scribbled down those notes, he and Engels had just finished their refutation of the Young Hegelians, The Holy Family. They went on to critically criticise contemporary German philosophy for the 400 printed pages of The German Ideology of 1844-45. Engels returned to the struggle against Idealism and mechanistic materialism with Anti-Duhring (1878) and Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy (1888). Then Plekanhov punctured the Idealists with his Monist Conception of History (1895), reinforced by Lenin’s Materialism and Empirio-Criticism (1909).

At each intervention, the politics of interpreting was front and centre. The Left needs to return to those exposés to exorcise the mumbo-jumbo spewing out of the New Age, evolutionary psychology, Deep Ecology and the Tao of Physics.

A comparable malaise from within academic Marxism is epitomised by the journal Thesis Eleven, which began in the late 1970s as an off-shoot of student activism. Thirty years on, the only change that its contents are likely to effect is to the promotional prospects of its authors. One title from the edition of August last year says it all: “Radical Finitude Meets Infinity: Levinas’s Gestures to Heidegger’s Fundamental Ontology”.

The German Ideology did not find a publisher until the Twentieth-century. Marx never considered publishing his rough notes. Given the confusion they continue to sow, the shame is that they survived the criticism of mice.

To approach a Materialist interpretation of Marx’s comment about interpretation and change, it is essential to study the opening Section of The German Ideology. Those 75 pages help us to grasp why we can interpret the world only by changing it, and hence ourselves, individually and as a species. Moreover, the change referred to in “Thesis Eleven” is not solely political. Marx was thinking about the totality of “sensuous human experience”, which Mao identified as the struggle for production, the class struggle and scientific experiment.

The aphorism is also historically misleading. From the pre-Socratics, Buddha and Confucius onwards, interpretations by philosophisers had been used to change the world. Philosophy had been the aether filling the space left by ignorance about natural and social processes. By the 1840s, the sciences were spelling an end to philosophising and quasi-theology. The last thing that Marx and Engels wanted to put in the place of such Idealism was mindless militancy.

Marx drafted the four volumes of Capital to write finis under speculation about the social metabolism. The path which Marx opened has to be cleared for each time and place. Lenin spent two years researching The Development of Capitalism in Russia (1899) to decide whether to oppose the Narodniks; he produced Imperialism, the Newest Stage of Capitalism to work out what to do in the wake of the collapse of the Second International. Mao investigated The Peasant Movement in Yunan to determine revolutionary strategy and tactics in the 1920s.

Nor could those revolutionary practitioners afford to spurn interpretation at the level of abstraction. Lenin spent weeks struggling with Hegel’s Science of Logic to arm himself for revolution in 1917. Mao penned On Contradiction (1937) while waging a two-front war against the Japanese and the Nationalists.

No doubt, the proletariat can move towards socialism without waiting for the algebra to transform values into prices. However, the campaign against Workchoices exposed the bankruptcy of change without interpretation. Stressing Howard’s nasty personality, Left grouplets rarely punctured the ACTU-ALP line about a fair day’s wage. By ignoring the chapters on labour-time in Capital, the grouplets left the working class with no explanation of why Workchoices is essential to the expansion of capitals in this era of globalised labour-times. Hence, the class is disarmed in the fight against Gillard’s Workchoices and her Construction Stasi.

Pensions (6 November)

The ALP’s ditching of social equality has come back to bite it on the stimulus package. On 8 December, single pensioners will find $1400 in our bank accounts.

A survey has shown that 40% of recipients are planning not to spend the grant. Instead, we will protect ourselves against the crisis in capital accumulation turning chronic, by either saving or paying off debts. Hence, the ALP’s abandonment of social equality is frustrating the multiplier effect.

Treasury should have anticipated that result from what happened in Japan in the mid-1990s when its government tried to escape the deflationary spiral by giving cash to the poor. In an economy with almost no welfare system, even those towards the bottom tried to save the handout.

The Australian pension system is skewed towards those who have an income stream, whether from work, superannuation or as interest on investments. The base pension rate is not reduced for the first $3,500 and then by 40 cents on every additional dollar of income. Retirees taking in $35,000, and with assets of $550,000, can get a one-dollar pension. Now they also get $1400. Changes in the 2007 budget opened the sluice gates to the well-to-do to fix their finances to qualify.

The pensioners most in need are single, with no income or assets, and renting commercially. This cohort ekes out each fortnight on the basic rate. They cannot reequip themselves. Hence, the fairer and smarter policy would have been to redistribute the $5bn package towards those most in need, giving $1400 on 8 December and the same again four weeks later. More significantly, the grant must be extended to those on unemployment benefit.

Boosting rental subsidies is hazardous because those supports are gobbled up by landlords. The solution here is for the state to provide accommodation.

Governments once had an administrative excuse for not enforcing a means test, arguing that it was more expensive to apply than it cost to give the same benefit to everyone. That is not so today in regard to pensions. The computer knows what percentage of the full pension we receive and it can be programmed to deliver that fraction of the $1400 into our accounts.

Speculation continues about a $30 pension increase during next year. If the very worst happens in 2009, pensions are more likely to be cut by $30 in the first of the horror budgets.

The prospects need to be set against the history of the Commonwealth pensions. Legislative approval in 1908 but they were not paid until 1910 because of a shortage of funds. They were pittances of ten shillings when the basic wage, itself miserable enough, was 48 shillings. Nonetheless, the Auditor-General in the 1931 attacked pensions for encouraging “laziness, drink, gambling, extravagance and waste.” Later in that year, all state-sector incomes were cut by 10 percent. “Equality of sacrifice” obliged a judge on £2,500 p.a. to go without 250 of those pounds – five times more than a pensioner had got before losing two shillings out of her pound a week. The $1400 handouts follow the precedents of treating everyone the same, which is to say, unequally.

Meanwhile, the best that can be said about the ALP’s budget-buster is that lavishing a billion or two on the better-off is less repugnant than outlaying those dollars on bullets, or even on an oenology laboratory for the lout-bourgeoisie at Melbourne’s Xavier College.

Mass Murdoch

To redress the left-liberal bias of the commercial media, the Board of the ABC has invited Rupert Murdoch to deliver the Boyer Lectures, starting on Sunday 2 November. As he observed in his 1972 A. N. Smith Lecture: “The public does not want to read propaganda: it wants to read objective news and informed comment.”

A promotional clip has Murdoch confronting the question of his Australianness. He gave up his Australian citizenship in September 1985 to secure broadcasting licences in the United States.

Nowadays, Murdoch can hold dual citizenship. The matter of his nationality was marginal since his loyalty has always been to the expansion of his capital.

However, while Murdoch, the individual, swapped allegiance, Murdoch as the personification of that capital in News Corp remained registered in Adelaide because Australian reporting standards were what Business Week (13 June 1994) called “lossey-goosey”.

Just after his nationality swap, the US journal Corporate Finance (April 1987) reported that News’s Annual Report for 1986 was a triumph of creative accounting. The exposure had been written for Forbes, which declined to publish so as not to offend Murdoch.

In March 1999, the Economist recorded the tangle of tax returns to conceal the liabilities of News, by then incorporated in the US State of Delaware (aka as “the State of du Pont”).

The Boyers will not be the first time that Murdoch has lectured us. In October 1994, he addressed the Centre for Independent Studies on “The Century of Networking”.

Murdoch quoted Solzhenitsyn that the essence of totalitarianism is “the destruction of collective memory”. Murdoch is a master of selective memory as he demonstrated in talking about how his father had sought criticism from the British tycoon Lord Northcliffe on how to improve circulation of the Herald where he had become editor in 1921. Murdoch junior made no mention of the sensation that did most to boost revenues – the Herald’s lynching of Colin Ross for the murder of the 12-year old Alma Tirtschke on 30 December 1921 in Gun Alley, off Little Collins Street.

The Herald and Weekly Times building on Flinders street became known as the Colin Ross Memorial, since Ross had paid for it with his life on 24 April 1922. In May, Victoria granted a pardon to Ross. We await Rupert Murdoch’s act of contrition for Ross during his Boyers.

The theme of the Boyers is to be The Age of Freedom, as it was in the 1994 Lecture. Murdoch had acknowledged the source of what passed for an idea in that talk as Peter Huber’s Orwell’s Revenge: The 1984 Palimpsest. Huber’s rewriting of Nineteen Eighty-Four is a paean to free markets, which Murdoch hastened to assure his listeners “are not monopolies”. Murdoch endorsed Huber’s faith that Orwell had been wrong because technology and markets were going to set us free.

It turned out that Orwell had been right to suspect that some of us were meant to be freer than others. In March 1994, he had replaced the BBC World Service on his Star telecasts into the Mainland. Within days of his Networking lecture on how technology would break down totalitarianism, Murdoch was in Malaysia offering its authoritarians a block-out switch over Star TV. In 1995, he provided Beijing’s Ministry of Truth with one. By July 1995, News Corp. had a joint venture with the People’s Daily. In his Lecture, he expected his access to “whole new audiences and markets” in China to be “goldmines”.

In the current crisis of capital accumulation, how free will the Asian Wall Street Journal be to comment on the thugs and swindlers running the People’s Republic of China, or on Murdock’s access to funds?

Reformism (28 October)

Accusations of “reformism” ricochet around meetings of Left grouplets. If only the proletariat would see through reformists and embrace our revolutionary program …

As the crisis in the expanded reproduction of capital unfolds, so does the need for strategies and tactics to protect working people. To devise these lines of action revolutionaries need to ponder what these alternatives of revolution and reformism mean in daily life.

An earlier piece discussed why state violence makes revolution a graveyard for socialists more than for capitalism. Does the impossibility of revolution succeeding here for any foreseeable future reduce the Left to reformism?

To answer, we must banish the Philosophically Idealist notion that “reformism” is a mistaken idea. Marx satirised the Young Hegelians for supposing that people drowned because their minds were full of the idea of gravity. If only they could free themselves from that idea, their lungs would not fill with water.

Mao was spot-on for saying that correct ideas do not drop out of the sky and not are innate in our minds. They derive, he went on, from social practice and from it alone. The catch is that so do incorrect ideas. That is why reformism is pervasive. Which social practice gives reformism its staying and pulling powers? Reformism is the hourly practice of the proletariat in our struggle for survival.

Who does more to maintain the rule of capital than wage-slaves selling our labour power. Without that exchange, no surplus value could be produced and capital could not exist. Telling workers to stop being “reformists” is like telling them to stop eating. By contrast, revolutionary practices form almost no part of the daily doings of any Australian worker.

Reformism also deserves to be distinguished from opportunism and careerism, which can be seen as more or less conscious choices.

Reformism is often associated with “trade union politics”, or what Lenin called “economism”. This limitation is not always consciously anti-revolutionary. One strand in the IWW rejected all forms of politics, not just parliamentary cretinism, in favour of direct action at the point of production. Their critics wanted to know how that focus could vanquish the state.

Two other forms of “economism” have competed for leadership the Australian labour movement. On one hand, a strategic economism found expression in the Communist Parties. They accepted that there could be no end to exploitation within capitalism. Their often militant campaigns taught, in word and deed, that there could be no such thing as a fair day’s pay and that the state was the instrument of class rule.

In tactical economism, on the other hand, unionists and politicians either ignore or deny those insights; instead, they plead for a fair-go through a state which they picture as a neutral umpire.

In practice, strategic economists are often compelled to do much the same but from a contrary frame of reference. One task for revolutionaries is make that frame more than rhetorical.

No demand is intrinsically reformist. For instance, the right to form a union becomes revolutionary if the bosses refuse and what wage-slaves cannot capitulate.

Reformism appeals because it is grounded in a solution to the here and the now. Hence, militants cannot argue someone out of reformism as they might change a friend’s mind about a dropped catch by showing the ball from a different camera angle. As with religion, the call to abolish reformism is the call to abolish the conditions that make it necessary.

Capitalising the banks (27 October)

Full and partial takeovers of banks are reviving interest in their nationalisation as a good in itself. This notion has significance here because the Chifley government’s failure to do so in the late 1940s served as a sop to “true believers” in the ALP’s milk-and-water Socialist Objective. Hence, it is important to understand that Chifley was not taking the first step towards socialism. He was capitalising manufacturing capitals. His banking bills organised capital just as his sending the army into the coalmines disorganised labour.

Chifley shared the labour movement’s distrust of bankers before an openly anti-labour government appointed him to the Royal Commission on Banking in 1935. His eighteen months as Commissioner allowed him to refine his prejudices as he gathered testimony about the banks’ reluctance to invest in manufacturing. In Britain, the 1931.Macmillan Committee had revealed a comparable problem.

As Treasurer from October 1941, Chifley used the Defence Power in section 51(v) of the Constitution to implement many of the Royal Commission’s recommendations. Knowing that those Regulations would lose their force during the transition to peace, Chifley secured Acts in 1945 to make them permanent.

This Act was crucial to reconstructing capitalism after the 1930s depression through four interdependent projects: unemployment of no more 5-7%; industrialisation (eg General Motors); powered by the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electricity Authority, to support a doubling in the population, half through mass migration. Controls over banks was essential for this program.

The 1945 Act made State and local governments bank with the Commonwealth, which gave its Trading arm more funds to assist manufacturing. For administrative reasons, this provision could not implemented until May 1947, whereupon the Melbourne City Council successfully challenged its validity in the courts. Only then did Chifley move to nationalise the banks, fearful that reconstruction was being saboutaged.

In 1949, nationalisation was also ruled ultra vires under Section 92 which reads that “trade, commerce and intercourse … among the States shall be absolutely free.” This decision required a majority of the Bench to contort the meaning of “free” from its original intent of not being subject to tariffs into meaning free from government restriction. ALP leaders seized on the judgement to pretend that socialism was impossible without a referendum to alter the Constitution.

What is the constitutional position today? The High Court in 1989 overturned the sloppy definition of “free” in a case about undersized crayfish. It appears that Section 92 is no longer an absolute barrier. However, a practical obstacle exists from Section 51 (xxxi) which says that property must be acquired on “just terms”. This provision was the deus ex machina in The Castle. If by some miracle, the banks were to be nationalised, we, the people, would have to pay their shareholders their full market value. The good news is that, if the banks had gone bust, we could pick them up for a song. The bad news is that before they had been devalorised, millions of unemployed would have nothing to sing about.

A government takeover of the banks would buttress the rule of capital by strengthening the state as its executive committee. However, the effect of nationalisation would be marginal without reconstituting the regulatory system dismantled under the Hawke-Keating.

Next: Reformism.

Fascism

Shouting “Fascist!” at the television whenever Howard appeared was a comfort, but neither effective nor accurate. The threats from WorkChoices and the anti-terror laws are part of the normal functioning of any dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, and continue to be so under the ALP.

The legal and cultural restrictions implemented by the Coalition were not fascism, or even a drift in that direction. They were examples of how a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie operates in a liberal democracy. Pointing up the reality of bourgeois democracy is more radical than bleating “fascist” at every right-wing parliamentarian.

Historical materialists attend to the balance of class forces at each phase in the accumulation of capital. We ridicule “universals” such as “power” when investigating social relationships just as we spurn “Ideal Forms” as the criteria for deciding what is or is not fascism. (My talk – “If it’s not fascism, what is it?” – can be heard via a link on my website.)

Proceeding from the conjunctural, we recognise that fascisms emerged in the early 1920s to deal with a specific crisis, namely, rolling challenges to the rule of capital from a revolutionary proletariat and peasantry. (It is worth adding that defeat of the Bolsheviks would have paved the way for a Russian variant of fascism.) From the late 1920s, a rupture in capital accumulation compounded that open war between classes. The German bourgeoisie answered the intersection of upsurge and implosion with an overt dictatorship, as distinct from the covert one during the Weimar Republic.

The gulf between those forces and those behind Workchoices are clear. Workchoices was not a response to any challenge from the working class. On the contrary, Workchoices got as far as it has because of the disorganising of the labour movement through the Hawke-Keating-Kelty Accords.

From the early 1980s, monopolising competition intensified the demands on capitals to lower the socially necessary costs of reproducing units of universal labour-time in commodities. This compulsion is the reality of globalisation. Workchoices encouraged bosses to meet that pressure through longer working days and weeks, speed-ups and unpaid overtime. Since 2007, that intensifying of the production of surplus value has been disrupted by blockages in its realisation as profit.

What has changed is not the government but the structured dynamics of the crisis. That development imposes more burdens on workers. Any resistance will generate require novel measures from the agents of capital. If we are closer to an open dictatorship under the ALP than under Howard it is because of a transformation in the crisis confronting capital.

Thus far, the crisis in accumulation has not provoked mass challenges. When it does, the ruling class will not return to inter-war style fascism. Hence, scanning the political landscape for neo-Nazi insignia will blind us to the hard core of the state. Its elite squads of police and in the armed services will give the agents of capital the time to establish novel forms of overt and covert dictatorship.

Socialists never forget that, although we recogmise that bourgeois democracy is a sham, it is the fascist for whom democracy is a bourgeois sham.

Next: A pack of reformists.

Revolution: not a dinner party (23 October)

The crisis in the accumulation of capital is reviving hopes that real existing capitalism is not the outer limit of human creativity. In the years of “free-market” triumphalism, socialists either shut up about revolution or flaunted “Revolution” to assert their purity over rival grouplets. Neither extreme is appropriate now.

The cusp of catastrophe is no time for chest-beating. Sounding further to Left than everybody else in the phone box is easy. Tossing the word “Revolution” around is easier still. The Rudd-Gillard prattles about an “Education revolution”, and Revlon brands its brightest apocalipstick “Revolution”.

Instead, a revolutionary response to the crisis begins from understanding the state as an instrument of class rule, that is, as class violence raised to an obligatory norm. That is why socialism becomes possible only after the capitalist state has been smashed. Even were a mass socialist party to take 60% of the vote, the guardians of capital would move to defeat such subversion by whatever it takes.

Almost every revolution in the modern period became possible only after the ruling class had lost its monopoly of violence. The Paris Commune in 1871 rose in the space, physical and political, vacated by the defeated Imperial army; the Bolsheviks were able to seize power because the Czarist regime had armed workers and peasants against the Austro-German-Turkish alliance; in the 1940s, similar opportunities appeared in Yugoslavia and Albania, China, Korea and Indo-China. Many of the volunteers for the International Brigades in Spain had been battle-hardened by capitalist states in inter-imperialist wars, which is why sending “brigades” to Venezuela is risible. Who on the local Left has so much as heard a shot fired in anger? Any who have are refugees from being shot at.

Among the rulers, one lesson from those wars and revolutions has been to de-laborise their military, keeping conscription as a last resort, going to almost any expense to avoid arming their own populations.

Engels saw that while the workers might form a militia, the bourgeoisie owned the horses. He explained away his fox-hunting as training to lead a proletarian cavalry against counter-revolutionaries. Today, the equivalent of horses are helicopter gunships – and who on the Left has a pilot’s licence?

Hugo Chavez is alive only because a sizeable segment of the armed forces came with him into the revolution. If political power does not grow out of the barrel of a gun, why is the opposition in Zimbabwe insisting on the police portfolio?

In Australia, capital has an absolute monopoly over armed force. Hurling oneself against a line of cops is, therefore, a game at which the police can beat us. Talk about revolution as smashing the capitalist state will return to the realms of scientific socialism when the SAS defects to the proletariat, or “revolutionaries” stop betraying our every move on their mobiles and over the internet.

For the moment, the Left has our time cut out exposing the state as a covert dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. The prospects of the present crisis leading to an open dictatorship are considered next. Steps towards averting that repression will follow.

Next: fascism

China: statistical inflation

(This item appeared in Crickey in mid- 2007. Its implications are pertinent than ever for an economy with a real estate bubble, a tottering stock market, a rotten banking system, no transparency, an artificial exchange rate, and a manufacturing sector built on snapping together imported components.)

Allan Greenspan warns that the bubble of the Shanghai stock market must burst. Ignoring his advice leads to a concern that a collapse in share prices could prick the real estate bubble and then meltdown the financial system. Behind that prospect hover cautions by Chinese authorities against over-heating in the real economy.

Yet, the Chinese miracle remains the envy of the world. Do the numbers stack up?

An article in the November 2003 issue of one of the world’s most reputable scholarly periodicals, the Journal of Political Economy, examined the statistical evidence between 1978 and 1998. Its author, Alwyn Young, turned “the extraordinary into the mundane.”

Instead of playing with the final figures published by central administrators, Young tracked how those results had been constructed from the numbers forwarded from the bottom. Lower-level officials were rewarded for meeting expectations and punished for failing to come in on target.

From time to time, the central authorities tried to correct the resultant errors. For instance, “the 1994 gross industrial output estimates were revised downward by about 9 percent.” That year, the government identified 70,000 cases of misrepresentation. Another reason for the gulf between the hype and the performance has been a “systematic understatement of inflation of enterprises.”

Young concluded that “the growth rate is not the highest in all recorded human history, but at levels previously experienced by other rapidly growing economies.” He reckoned that labour productivity had increased by 2.4% a year on average. Total factor productivity has risen by only 1.4%, which was “respectable but not outstanding”.

More recently, other experts have doubted the high-flying numbers. In the China Economic Review (2004), a researcher from the Beijing Statistical Office discussed the confusion following the switch in national accounts from Soviet-era material product calculations to the United Nations’ System of National Accounts. The latter includes more services – including the Shanghai Stock Exchange?

In the same issue, Carsten A. Holz reported other criticisms by Chinese officials of the statistics. Holz complained that none of critiques allowed a researcher to reconstruct household consumption. Furthermore, the relationship between the GDP component of household consumption and the underlying data varied from year to year. Hence, comparisons of Chinese GDP figures across even brief spans of time remained unreliable.

In light of these uncertainties, how can investors be expected to put a realistic price on shares? Meanwhile, Young and the other sceptics offer reasons for taking a harder look at the writing on the wall.

Back to the plan?The collapse of the Soviet Union is misrepresented as the failure of Marxism and as proof that there can be no alternative to the force of the market. The first half of that claim is wrong. The second half remains to be refuted by a real existing socialism. The crisis in capital accumulation is no reason for Marxists to swing from humiliation to hubris.In regard to the implosion of the Centrally Planned Economies, the worst that can be held against Marx is that he did not bequeath a blueprint for building socialism. Had he and Engels attempted to do so, they would have denied the materialist foundations of their work. All socialists are utopian about where we want to go, but Marxists are supposed to be scientific about how to get there. No one can come up with effective answers to problems we have never encountered. To think otherwise is to worship the Ideal Forms of Philosophical Idealism.Hence, Stalin’s pamphlet Economic Problems of socialism in the USSR is more useful to debates about planning than are the fifty volumes of Marx and Engels and the forty of Lenin combined.The first five-year plan from 1928 was cobbled together in response to the chronic imbalance between rural production and urban consumption. Collectivising agriculture was an afterthought. The planners had no better guide than Marx’s account of the development of capitalism in Volume II of Capital where he tracked the interflows between Department I (production goods) and Department II (personal consumption goods). (W. W. Leontief got the fake Nobel in 1973 for turning Marx’s model into input-output tables.)Planners did well on massive projects within Department I, such as constructing the Dniepner Dam. State planning is also fairly effective at managing scarcity through rationing. Hence, Cuba is likely to weather a global meltdown better than the US of A.Where Centrally Planned Economies stumble is in supplying the right number of screws of the right thread to the right place at the right time. If the planners prescribe a volume of screws, they get a billion tiny ones; if they control by weight, screws arrive the size of hammers. It was no joke that one theme song of China’s Cultural Revolution was “I want to be a revolutionary screw”.Worker control, by itself, is no answer to the problem of the millions, or the problem of intermediate goods. A meeting in a shirt factory cannot know how many tractors another factory should make to harvest cotton that wont be sown for three more years. (Capital plans through the anti-competitive device known as the firm, now the multi-divisional/multi-national corporation.)The prospects for planning led to a technical econometric dispute in the UK during the late 1930s when F. A. von Hayek argued that no one could anticipate the needs of an expanding economy. Marxists believed that they had proved him wrong mathematically. Algebra, however, buttered no black bread.The political fallout from the failures in socialist planning is with us as we confront systemic market failure. In the 1930s, the Left pointed to Soviet planning as the solution to mass unemployment. That promise is not going to convert anyone to socialism today. If socialists seek to replace capitalism, we have to face up to ‘the problem of the millions’.A preliminary step thither will be to absorb the materialist precept that no human activity can be free of failure. As Engels put it: “Each victory, it is true, in the first place brings about the results we expected, but in the second and third places it has quite different, unforeseen effects which only too often cancel the first.”

Next: Getting there.

Greed

The Right-wing Reverend Rudd has been preaching against “extreme capitalism” and its driving force “greed”.

This time last year, the cherub was singing from a different hymn sheet. Then, it was, “Get real. This is the twenty-first century”. Rudd aimed that profundity at workers calling for industrial action beyond individual enterprises and during only bargaining periods. Rudd accused them of living in the past when strikes might have been justified because capital was still predatory. That era had passed: “Get real. This is the twenty-first century.”

At the time, Crikey carried my catalogue of what else Rudd would have to throw out to get real in this brave new world. First to go would be the Eighteenth-century Adam Smith, followed by the Nineteenth-century joint-stock company and its successor in the corporation; next in line for the chop were its twentieth-century restructures into multi-divisional and multi-national conglomerates. You could not get more extreme in your anti-capitalism.

Does it matter if Rudd is a worse theologian than an economist? Perhaps, because there is an economy but there is no god. The choirboy’s brain is like a flypaper for discredited bourgeois excuses. He presumes that good capitalism is built on restraint, with profit as the reward for abstinence. To this fairytale he attaches the pretence that “profiteers” were the naughty profit-takers, distinct from those stuck with average rates. (This fallacy is dissected in ‘Don’t pick on bankers” and The market for futures”.)

The current crisis is not the outcome of greed any more than greed embodies “extreme capitalism”. If anything, the reverse is true. Extreme capitalism is when capitalists outlay as little as possible on their own wants. Marx identified a Faustian dilemma between the desires of individual capitalists for conspicuous consumption and the need of aggregate capital for expanded reproduction.

The capitalists can either squander all their profits on champagne and jewels, or they can reinvest the profits they have appropriated from their workers so as to extract even greater profits from their labour power, and on it grows. If capitalists spend up, they cease to personify capital. If they reinvest, they drive capital to its extremes of expropriation and monopolising.

In short, greed disrupts accumulation. It is neither extreme nor temperate capitalism. It need not be capitalism at all. Of course, capital produces needs in workers in order to realise profits from the sale of the products embodying their labour power. That drive to satisfy the needs of capital by stimulating debt is at the heart of the current crisis. (For the Rev. Clive Hamilton’s version of “greed” as the root of all evil see the attached review of his Affluenza.)

By focusing on ethical flaws, Rudd is fiddling with the conventional ignorance about a Protestant ethic’s giving birth to capitalism. That view is attributed to the German sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920). Although the proletariat terrified Weber, he was too intelligent and honest to pretend that the class struggle wasn’t happening. He was also too well informed to believe that capitalism could thrive on an idea. On the contrary, he saw that the Protestant ethic had flourished only because peasants had been subjected to labour discipline, what he described as “a long and arduous process of education.” That indoctrination followed the students’ being freed from the burden of a patch of land from which they could live without becoming wage-slaves.

Rudd didn’t understand capitalism a year ago and he doesn’t understand its il-logic any better now. What he knew then, and knows more keenly now, is that he has to protect real existing capitalism from itself. As the personification of the bourgeois state, he is paid to organise capital and to disorganise labour. To those ends, he and his ilk will go to any extreme.

Next: To be a dinosaur (the crisis willing).

To be a dinosaur

Dinosaurs lasted 26 million years. They came in every size and shape and all the colours of Joseph’s coat. So, when Imre Salusinszky in 1997, and John Grayling last year, dismissed me as a “Marxist dinosaur”, I sighed “If only…”

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the toadies chorused: “Marx is discredited”. To which Marxists replied: when, and for what, did your crew ever give him credit? Das Capital had been “discredited” in 1896 by Eugen von Bohn-Bawerk’s Karl Marx and the close of his system. Since then, thousands of books have reasserted the close of Marxism, without understanding either Marx, or this early critic.

The relentlessness of their onslaught has not been aimed at Marx but at depriving proletarians of our keenest intellectual armoury. From nowhere else can we learn the three keys to capitalism: one, class struggle is waged every second of every day – at work, asleep and at play – to maximise the exploitation from capital’s purchase of labour power in units of labour time; two, this exploitation means there is no such thing as a fair day’s pay; thirdly, the state enforces this exploitation.

Capitalism keeps Marxism creditable. For as long as capitalism is around, Marxism is in no danger of extinction. Meanwhile, media blather about a swerve back to “socialism” by bank nationalisations and welfare spending is as ill-informed as was its “discrediting” of Marx. Hence, those of us who need Marxism in current battles spurn both versions to remain clear about what Marxism can and cannot offer.

First, Marxism is a sub-set of historical materialism, the one which explains capitalism. Historical materialism, in turn, is a sub-branch of materialist dialectics. The Neo-Darwinian synthesis is another. Because both inquire into aspects of our species, some of their concepts and evidence overlap, but they are neither substitutes for each other, nor can one suborn the other. Marxism has nothing to say about the extinction of dinosaurs and Darwinism is silent on the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.

Secondly, Marx’s analysis of capitalism is specific to that mode of production, and not cannot be extrapolated onto pre-class societies, or even to slavery or feudalism. Yes, what Marx and Engels revealed about the structured dynamics of capitalism is rich with insights about how one might investigate other systems of class exploitation, but those clues are side benefits, not a matrix.

Thirdly, Marx provided only the starting place for understanding capitalism. His insights are essential but never sufficient. We must continue their investigations, as Lenin did in the late 1890s to determine whether a proletariat was emerging in Russia. To do so, we must remain critical about what Marx, Engels and Lenin uncovered. What matters is not what they “really” said. The point is whether their analyses were true at the time, and, more importantly, do those elements relate to capitalism now.

One feature of Capital are the passages which splotlight every twist in the current unraveling of capital. Those quotable quotes are valuable not as evidence for his prescience but only as indications of how Marx integrated such behaviours into his account of the il-logic in the expansion of capital.

How can Capital still be crucial 140 years after its publication? The answer is not that Marx was smarter than Adam Smith. His advantage was that he lived through the establishment of modern capitalism whereas Smith had died before the proletariat appeared.

Unlike Smith, Marx did not write “political economy”: he critiqued it – as he did aesthetics, anthropology, history, philosophy and theology. Unless Marxism remains critical it becomes a nullity. One performance enhancer would be for Gillard to ban it from the education system. However, for as long as Marxists cleave to “class struggle”, “exploitation” and the class bias of the state, we won’t need bourgeois agents like her to keep us subversive.

We can remain socialists without being any kind of Marxist. Few socialists have ever been Marxists and most never will be. But you can’t stay a Marxist without being a socialist.

Next: Back to the plan

False Nobel

The “Nobel Prize for economics” is as mendacious as any of the scams exacerbating the current crisis. In 1895, Nobel’s will provided for five Prizes: Chemistry, Literature, Medicine/physiology, Peace and Physics. This week’s award for economics has as much to do with the Nobel Prizes as peace-making has with Nobel’s marketing of dynamite.

If the prize did not originate with a merchant of death, who is responsible? From 1969, the Swedish National Bank funded of the Alfred Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Science. This move extended the Bank’s defence of capitalism. On the home front, the bankers were campaigning against the government’s socialism by stealth through superannuation. Across the world, the Bank promoted economic correctness. The “Nobel Prize in Economics” is a propaganda weapon for the “free market”.

To restore balance, the ABC should tag every mention of it with “fake”.

Who has got it and who has been passed over underline the ideological intention. In 1974, the Bank gave the award to the godfather of the free marketers, Friedrich August von Hayek.

They covered up the fact that he had not published a word of economic science in 35 years by splitting the prize money with the social democrat Gunnar Myrdal, a Swede.

After honouring the venerable and the brilliant, the committee were forced to reel in complete outsiders such as John Nash, the mathematician of A Beautiful Mind.

Notwithstanding this elasticity in their demand, they have had to scrape the bottom of the barrel.

Two omissions highlight the politics. First, John Kenneth Galbraith was never much of a technician but was far more distinguished an analyst than many of the winners.

Multiple biases collided to exclude the neo-Ricardian Joan Robinson, (1903-83), a woman and on the extreme left. She made laughing-stocks of her male colleagues, turning down a prestigious post on the grounds that she could not sit on the board of a journal which she could not read. She disparaged the econometrics that earned most of the winners their tickets to Stockholm as little more than calculating the price of a cup of tea. In the eyes of the clerisy, her crime was greater. Had she not demonstrated in The economics of imperfect competition (1933) that monopolising, and not free trade, rules the market?

The 1997 winners were Robert Merton and Myron Scholes who got the money for mathematising derivatives, which they put to work in their hedge fund, Long-Term Capital Management. When they lost $4.6bn., the Federal Reserve had to rescue the global financial sector.

Who most deserves this faux Prize in 2008, the year when the phonies are too multitudinous to be bailed out? Surely, the frontrunner is whoever – academic, journalist or PR consultant – dreamed up re-badging the expansion of the past thirteen years as a “plateau” not a “boom”. Reminded that all previous booms had gone bust, this promotional genius shot back: “No, this round of growth need never end because it is not a ‘boom’. It is a ‘plateau’. There are undulations, but neither precipices nor peaks.”

This flash of geographical insight had been foreseen by Marx: “On the level plain, simple mounds look like hills; and the imbecile flatness of the present bourgeoisie is to be measured by the altitude of its great intellects.”

Next: O, to be a dinosaur

If she blows? (11 October)

If it is dodgy to speculate about the timing of, or the immediate trigger for a depression, six consequences can be predicted with almost 100% accuracy.

>Above all, a collapse of real existing capitalism is not going to move the world one toenail closer towards being a kinder place in which to live.

On the contrary, a depression will make every problem worse. Those whose labours paid for the boom will pay seven times seven for its collapse.

>On the macro-economic front, the normal process of oligopolisation will spike.

The benefit of a depression to capitalism as a whole is, as the conservative economist Joseph Schumpeter recognised, from a gale of creative destruction. That means the destruction of firms of the size of GM and Ford.

>At the micro-economic level, even a serious recession will shatter generations X and Y, who have never known more deprivation than retail envy.

Their harrowing will be much harsher than poverty was on the 1930s victims who had been weaned on frugal comforts, not expecting super-affluence. Far fewer will know how to feed themselves once they are no longer compelled to eat out because of their excessive hours at work.

>This material deprivation will provoke identity crises.

Bourgeois individualism has shrunk from being defined in the Renaissance by what one creates, to what one makes, to what one owns, and now to whatever gadget one has most recently bought. Self-esteem is reduced to the exchange of credit for a commodity which loses its prime use value by being purchased. What happens to the sense of self when the buying has to stop?

>The social consequences of an end to retail therapy will rip through civil society.

Reflecting on the recession of the mid-1970s, the then head of CRA, Sir Roderick Carnegie, warned that “A society raised on champagne tastes may not be a polite or a pleasant one if it is reduced to a beer income.” That shadow over bourgeois democracy is larger in this era of anti-terrorism.

>The environmental consequences will be catastrophic.

Although the burning of fossil fuels and the use of other non-renewables will be cut as a result of the slashing in effective demand, the corporations and the poorest alike will be driven to plunder the wealth of nature for survival. Expensive renewables will be out of the window. It remains to be seen how many promoters of carbon markets will be happy to pass the fate of their goddess to the traders who brought on this pillage.

That skim through the consequences leaves us with a pendant to the pivotal question: if capitalism can indeed collapse, can it also rise again?

To approach an answer, we must look again at the 1930s. The conventional belief is that Roosevelt’s New Deal rescued the US. In truth, the downturn of 1937-8 was as steep as that at the start of the deflationary cycle. What dragged the world out of depression was global war.

That gale of destruction lost some of its creative promise at Hiroshima.

(Crikey declined an earlier version in July 2007 as “too depressing”.)

Next: A dinosaur’s revenge.

“19 October 1987” (9 October 2008)

The attention being lavished on bank failures and failing bailouts deflect attention from another faultline. The US economy remains dependent on the in-flow of funds to pay for its imports and to fund its three tiers of government. Here, the parallel is not with October 1929 but with October 1987.

That plunge had its source in the redemption of the US economy through driving the less productive firms to the wall through an appreciation of the US currency. That policy made imports cheaper and exports harder to sell. Devastation created the rust-belt.

By the start of Reagan’s second term in 1985, the purge had done its work. US capital and its competitors both needed to wind back the value of the dollar. On 22 September 1985, at the New York Plaza Hotel, the “Plaza Accord”. The plan was to ease the dollar down by 10-12%. Instead, it fell by around 50% against the Yen and the Deutschmark.

A thought experiment helps us to understand what happened next. You are the Sumitomo Bank with investments in the US stocks and bonds. The dollar loses a quarter of its value against the Yen. Instead of owning 100 units, Sumitomo now owns 75 units. All indications are that the dollar will continue to slide. Do you leave money in New York and Washington in the hope that the exchange rate will eventually move in your favour? Or do you pull your investments out and taking the 25% drop rather than risking a 50% loss?

While Sumitomo is pondering what to do, so are all the other investment houses. They are watching the exchange rate and each other. If you are going to exit, you need to get out first to minimise the dangers from a run on the dollar driving down the value of your investments even more.

The flight from the dollar precipitated the plunge on Wall Street on “Black Monday”, 19 October 1987. Catastrophe was averted when the Bank of Japan and the Ministry of Finance instructed Japanese institutions to bear the unbearable by carrying the losses to preserve the global system.

One medium-term consequence of being burned was to encourage smaller investors to look closer to home, thereby feeding the real-estate and stock-market bubbles which went wild until the early 1990. Thereafter, Japanese capital entered into a deflationary cycle from which it still has not escaped, with an interest rate of 0.5%, an effective minus.

A longer-term outcome is that the Japanese were no longer in any position to rescue global capital. Moreover, they were no longer the ones pouring most savings into the USA. That place has been taken by the Mainland Chinese. And that should make us very afraid. China’s financial sector itself conceals an Everest of bad debt and has no guardians comparable to Japan’s in 1987 to marshall financial resources.

Against the tide the declines, the Greenback has been appreciating. So far, so good. The worst case will be a falling US dollar with a collapse of US stocks. That combination will encourage overseas investors to cut and run. One impediment to that solution will be finding a better hole in which to hide. Buy gold!

Next: If she blows.

Not the 1930s (9 October)

Eleven years after the Asian financial tail-spin and twenty since a flight of funds cut 30% off stock prices, central bankers are running up warning flags about the fragility of their global system. As far back as June last year, the International Bank of Settlements raised the stakes by using the D-word – a Depression of 1930s dimension – not just a recession like that of the late 1970s.

Returning from two years in Toyko in April 1990, I waited for the bursting of its real-estate and stock-market Bubbles to torpedo the world economy. Instead, Japan’s technocrats navigated through a protracted deflationary cycle by ignoring the advice of free-market economists to deliver a short sharp shock of the kind with which Jeffrey Sachs was harrowing post-Soviet Russia.

Having got Japan wrong, and not keen to join those commentators renowned for predicting eight of the last three recessions, I stopped asking “When will capitalism collapse?”, instead, pondering the question “Can capitalism collapse?”

Whatever happens next will not be a replay of the 1930s.

The first obvious difference from the 1930s is that the world economy is now several times larger. The force needed to stop its expansion will have to be that much larger than it was around 1930-32. The momentum of the current system might allow it to keep from stalling while growing at a lower rate.

Connected to this increased in size is that the global order now has three principal centers, Europe, North America and East Asia, against three halves 80 years ago. In the last 15 years, the global economy has sometimes got by on a single engine until at least one of the others restarted.

Two points of similarity with the 1920s remain. The first is that the Wall Street Crash of October 1929 was a symptom of the depression, not its cause.

The flood of funds into the stock market had followed the drying up of opportunities to gain average rates of return from investing in the production of surplus value. One instance of this over-supply today is that, were all the car plants in North America to close down, the auto factories in the rest of the world would be able to roll out more vehicles than there is credit to buy them (ie, “effective demand”). Also like then, any tripwire will be in the financial sector because its bubbles have resulted from the latest bout of excess manufacturing capacity. The sub-prime crisis is not infecting the physical economy. That is where it started.

On top of these objective factors comes a psycho-sociological reason why the triggers for another depression will not replicate October 1929. Too many people are watching that possibility. Danger spots erupt wherever no one with the power to act is looking. The cliché that those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it forgets that those who are fixated on a version of the past are condemned to be run down because new things keep happening. That’s dialectics for you.

Next: October 1987.

A fiction on fictional capital

House of All Nations, the 1938 novel by Christina Stead, described by The Oxford Companion to Australian Literature (1994) as “epic in scale, encyclopaedic in detail, cinematic in form, it is a scathing account of the world of international finance, although once again the eccentricity of private obsession rather than generalized class interests holds the foreground.”

Stead extracted the following epigrams from her characters to form an opening “Credo”:

Jules Bertillon, the protagonist and a merchant banker:

No one ever had enough money.

There’s no money in working for a living.

If all the rich men in the world divided up their money amongst themselves, there wouldn’t be enough to go round.

Here we are sitting in a shower of gold, with nothing to hold up but a pitchfork.

Woolworth’s taught the people to live on nothing and now we’ve got to teach them to work for nothing. Every successful gambler has a rentier sitting at the bottom of his pants.

It’s easy to make money. You put up the sign BANK and someone walks in and hands you his money. The façade is everything.

William Bertillon, his brother:

If there’s a God, he’s more like Rockefeller than Ramsay McDonald.

A speculator is a man who, if he dies at the right time, leaves a rich widow.

E. Ralph Stewart:

Of course, there’s a different law for the rich and the poor; otherwise, who wold go into business?

Michel Alphendery:

The only permanent investment now is in disaster.

A self-made man is one who believes in luck and sends his son to Oxford.

Comtesse de Voigrand:

There are poor men in this country who cannot be bought: the day I found that out, I sent my gold abroad.

Henri Leon:

Everyone says he is in banking, grain, or peanuts, but he;’s really in a dairy.

Dr Jacques Carriere:

Patriotism pays if you take interest in other countries.

Frank Durban

With the revolution coming, there’s one consolation – our children won’t be able to spend out money.

Globalisation (8 October)

To announce that “we live in a global economy” has all the explanatory power of saying that “The earth is pretty much round.” The implosion of world finances both confirms and challenges the conventional wisdoms flowing from two decades of gabble about globalisation. On one hand, liabilities continue to spread throughout the banking sector, from Boston to Belgium. The slicing of sub-primes to reduce risk has infected every cranny of the system, even Iceland.

On the other hand, the claim that globalisaion has rendered nation-market-states redundant has taken as big a battering as the Australian dollar. Who, if not nation-market-states, have been riding to the rescue of the globalisers? Those financiers got their $700bn bailout via the US imperium, not from the corporations that were supposed to rule the world by themselves.

One rung down from the big picture of a borderless – indeed, a “flat” – world, we find that even the most powerful regional grouping, the European Union, has fractured. Germany broke ranks to guarantee its saving-bank deposits. At most, its oldest members are “sticking apart”.

“Globalisation” became like an overcoat concealing a multitude of ignorances, many of them willful. The globalisation pap could get traction because the Left had submitted to the bourgeois phrase “nation-state”, which omits the very practice – “market” – that capital needs is state apparatuses to uphold. Hence, Marxist-Leninists need to argue in terms of nation-market-states and imperial-market-states.

Nation-market-states are there to preserve the interests of clusters of capitalists. Above all, they exist to sustain class rule inside their own borders. To repeat: the state organises capital and disorganises labour.

Ellen Mieskins Wood reminded us that capital needs the state in ways that slavery and feudalism do not. Surplus value has to be realised in sales from as widespread a market as possible, before the profits must make their way back. Those pathways have to be policed against competitors and workers.

Not all nation-market-states are equal. Hence, globalisation has weakened some of them, both within their home sphere of operations, and also in relation to the empire-market-states, primarily, the US of A. However, that hollowing out could not be allowed to go too far. The dangers were as exposed during the 1997 Asian meltdown as that crisis unravelled the IMF’s “tough-cop” packages of structural adjustment which had been compelling governments to abandon swathes of social action, such as health and education.

The revolt against Indonesia’s Suharto precipitated a new stratagem from the World Bank. The soft cop swung its checkbook behind building “effective” states, meaning those that could control their populations when they rose against the economic blows.

Each crisis has its contingent features. Globalisation is not one of them since capitalism was born global in the Venetian and Dutch merchants, to be weaned on the triangular trade of slaves and sugar/cotton from Africa to North America and onto England. Nor is there anything new in global reverberations from financial flops. For instance when bad loans in the Argentine rocked Barings Brothers in 1889, the shockwaves hit Marvellous Melbourne; gold bars had to be rushed from Paris to stabilise “The City” of London.

Next: Not October 1929.

The housing question (7 October)

With mortgages the tripwire for the sub-prime implosion, clarity about the relationship between home-ownership and capitalism is overdue. In brief, a mortgagee does not become any kind of capitalist with the final interest payment.

Two examples demonstrate the long-standing confusion of owning personal property as capitalist. At the 1949 elections, the Minister for Post-War Reconstruciton in the Chifley government, John Dedman, lost his seat after declaring that the Labor Party was not interested in creating a nation of small capitalists by promoting home-ownership. Sixties radicals joked about becoming POMs – Property-Owning Marxists – when they took out a mortgage. Both statements represent the triumph of petty-bourgeois moralising over scientific analysis.

Owning one’s own dwelling cannot make you any kind of capitalist, even if that house is a penthouse in Dubai. In that case, you almost certainly needed to have been a big capitalist to afford such an abode. More significantly, paying for it could put an end to your being a capitalist by soaking up all your funds for reinvestment.

For the rest of us, rent is one of the socially necessary costs in the reproduction of our labour power. We struggle to make sure that our wages cover that outlay, along with food and clothing. If rents or interest rates go up, so does the pressure on wages. Equally, if all the workers in a labour market were to posses their own dwellings, employers would strive to push down wages until the homeowners would be no better off than those in the rental sector. The outcome, of course, depends on the relative strengths of the contending classes.

In 1936, the South Australian government demonstrated this principle by setting up the Housing Trust with low rents to reduce average wages in order to attract manufacturing to the State.

Erstwhile head of Treasury and the Reserve Bank, Bernie Fraser, has never owned his own house, arguing that it is more profitable to rent and to invest his savings. High returns are more likely with his skills and contacts. However, his exceptionalism underlines that homeownership is not the first step to becoming a capitalist.

What about the situation that more Australians have put themselves in lately by buying into a rental property? In those cases, they benefit indirectly from the values added elsewhere in the economy, making them rentiers. Had they set up a small building firm, you would live off the direct exploitation of their employees, and indirectly from the purchasers, so that they become part-capitalist and part-rentier.

Australian workers seek homeownership to escape the costs and disruption from eviction. In addition, owning your own place has been insurance against impoverishment in old age. Both reasons remain part of the socially necessary costs of reproducing labour power. They are not shortcuts to living off the labour power of others.

[Engels wrote a booklet The Housing Question which should be on every re-reading list. However, the sections dealing with ancient issues can be skipped by most readers.]

Next: Globalisation

The market for futures

If Main Street despises bankers, then it loathes the brokers who trade in futures. Bankers, at least, assemble the money necessary for expanded production. Traders in futures make their fortunes by speculating. Worse still are the brokers who trade in financial derivatives.

Allocating dealers to their respective circles in hell tells us nothing about what capitals must do to survive. So, instead of consulting the petty parasites at the St James Ethics Centre, we have to ask how a trade in futures can help the corporations that produce pork or plastics. In finding the answer, we shall also glimpse how Wall Street learnt about futures and derivatives from the Chicago commodity market, developing since the 1860s.

The point of capitalism is to end up with more money to re-invest than you had when you started. Capital cannot expand merely by exploiting labour. The surplus value that results from that relationship is useless until the commodities in which it is embodied are sold. Nor is selling enough. For instance, a corporation marketing roses has to sell its bunches while they are fresh, otherwise, they are marked down and the sale price will be less than the cost of production. Here is one way in which a futures market helps capital. Instead of selling physical flowers in spring, the corporation sells virtual flowers in winter. This deal means sharing the profit with the traders and possibly accepting a lower return than if the agribusiness had waited to see what price it could get six months hence. The advantage is that the corporation is guaranteed a predictable level of income.

Suppose now that that corporation has sold its future roses at a price which delivers the average rate profit. Its managers’ worries are not over. They still have to lay hands on that money in the shortest possible time. Business is conducted on credit of thirty or more days. While waiting for the income to wind its way back from tens of thousands of florists, the growers depend on their banks. The longer it takes for the sales money to arrive, the more interest the producers pay out of their profit.

To complicate matters, corporations plan their finances much more than thirty days ahead. QANTAS orders a fleet of 797s in 2005 to take delivery in 2009. The final cost for those aircraft fluctuates with the turbulence of the global economy. Hence QANTAS buys “money” at a future price. The traders allow it to bet against an unfavourable shift in the terms of its contract, for example, as the exchange rate swings up and down.

To see how traders service capital is not to accept that those go-betweens provide a social good. There are no “human” interests, only the interests of specific classes. Within the capitalist class, those interests are fractured between kinds of capitalists who cannibalise each other for the largest possible slice of the surplus value from us wage-slaves. Swindling and cheating each other remain the order of the day for production as much as in low finance.

Next” The Housing Question

McValue

[An earlier version appeared on Crikey, 20 July 2007]

McBankers justify their multi-million dollar bonuses as rewards for “adding value”. That phrase went feral among private equity merchants just as their world began to implode in mid-2007.

But what kind of value? To answer “the share price” makes a $90bn takeover sound cheap, at least, aesthetically. Yet public affairs consultants had succeeded in re-branding “price” as “value”, and vice versa.

That prestidigitation is replete with paradox. Three instances can be tracked across three domains, first, economic theory, secondly, into accountancy, and finally through stock-broking.

From the 1870s, the jettisoning of “value” as a metaphysical concept was the launching point for the Neo-Classical economists, the progenitors of today’s orthodoxy. What mattered to them was not some intrinsic value in a commodity, but its price as determined by supply and demand. Out went Marx’s definition of value as congealed labour time, and in came the marginal utility ability to determine the price of a cup of tea. To reach this position, the neo-Classical turned their backs on Adam Smith.

Then, in 1926, the neo-Ricardian Piero Sraffa showed that the Neo-Classicals had been calculating capital and profit in terms of each other. For the next fifty years, the brightest and the best of them tried to redeem their premises. Failure led them to pretend that the circularity in their algebra was merely “technical”.