by Frederick Carlton Curr (with Preface ‘This Whispering in our Hearts‘ by Ian Curr).

Edited by Eleanor E. Freeman

Preface to online edition by Ian Curr

ISBN 0646368397

CONTENTS

Preface to online edition –‘Whispering-in-our-hearts‘ – an acknowledgment of country never ceded by Ian Curr

Foreword by Eleanor Freeman

PART ONE

Edward Micklethwaite Curr’s Memoranda

1. Origins

2. Edward Curr

3. Edward Micklethwaite Curr

PART TWO

19th Century

4. Marmaduke

5. Merri Merriwah and Gilgunyah

6. Abingdon

7. Reminiscences

8. Family Stories

9. Harsh Times

PART THREE

20th Century

10. Family and Property

11. Fred’s Travels

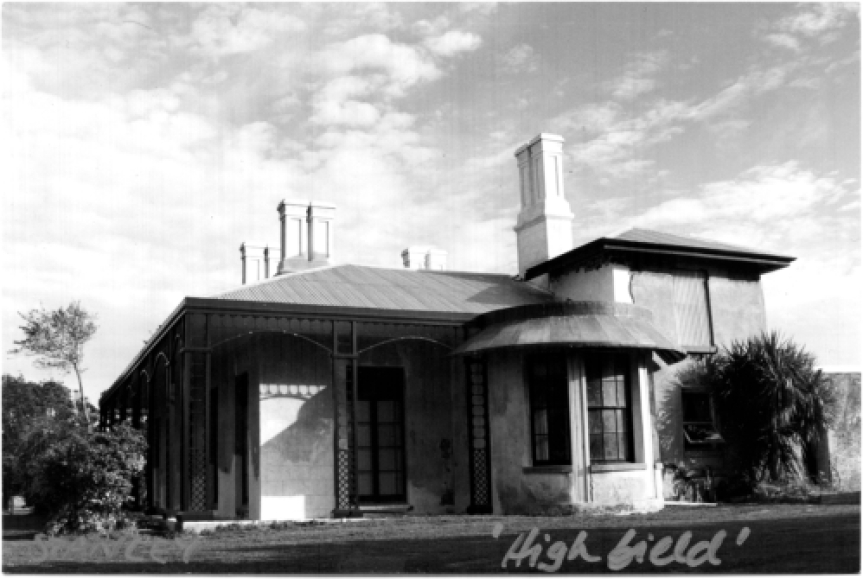

12. A Visit to Highfield

Afterword

__oOo__

Preface to online edition – ‘This Whispering in our hearts‘ – an acknowledgment of country never ceded by Ian Curr

"The trouble is that once you see it, you can't unsee it.

And once you've seen it, keeping quiet, saying nothing,

becomes as political an act as speaking out.

There's no innocence. Either way, you're accountable."

Arundhati Roy

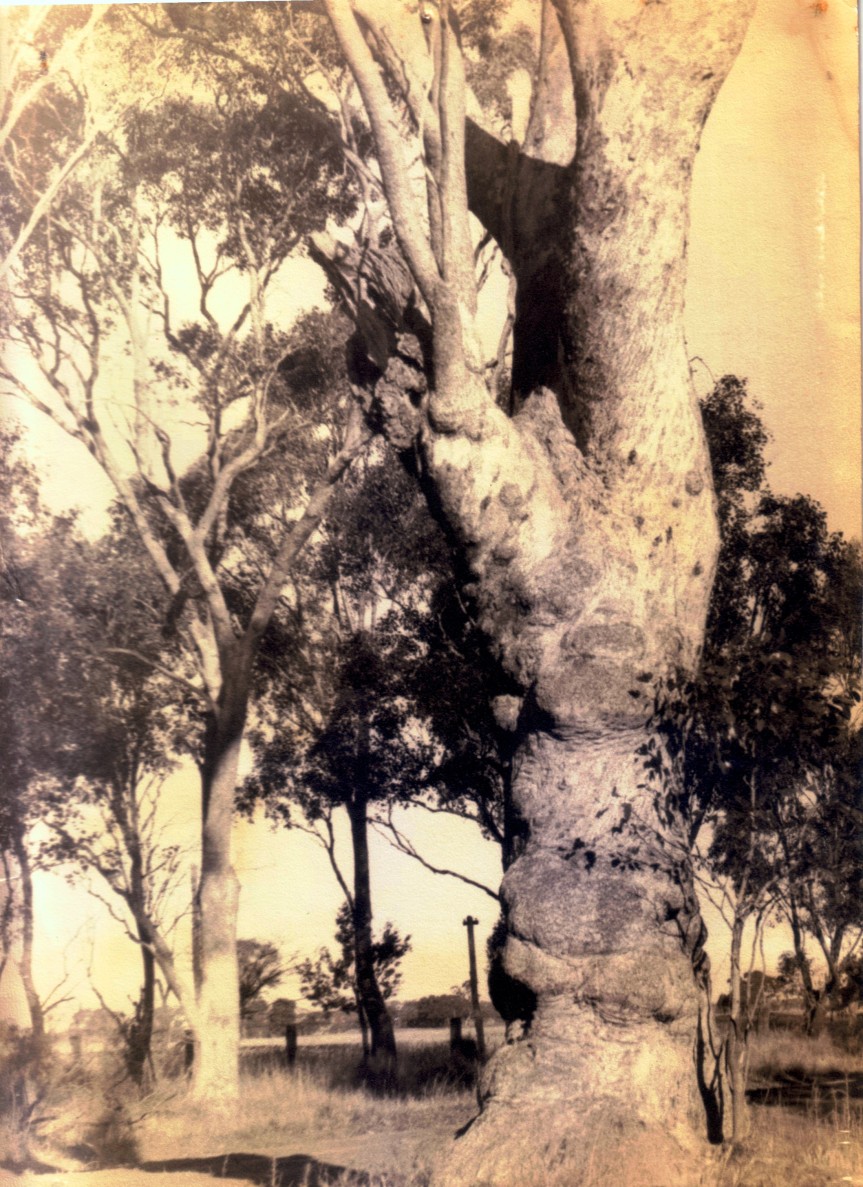

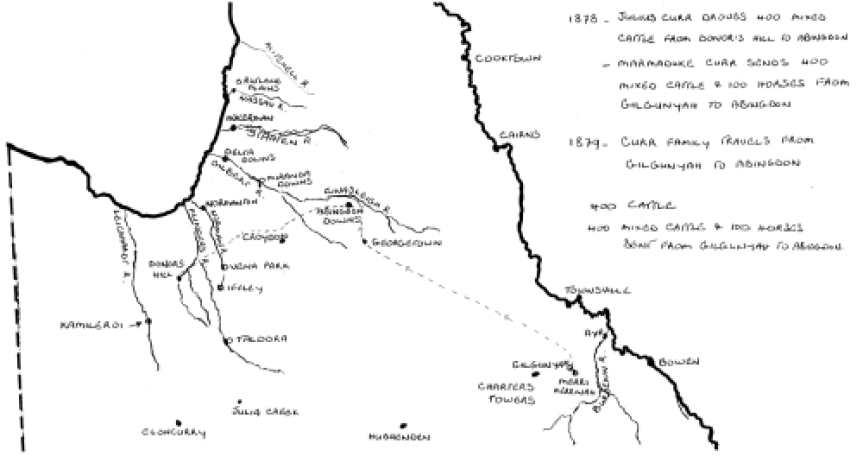

In Chloe Hooper’s book The Tall Man the Doomadgee family describes the period of the 1860s and 70s in North Queensland as the Wild Time. I describe here Curr family involvement in ‘Contact Wars‘ in the Gulf Country. Members of the Curr family moved to North Queensland in 1862. My grandfather, Fred Curr (b. 1865), grew up on Abingdon Downs station on a tributory of the Einasleigh River near the gulf of Carpentaria. The property is bounded by the Einasleigh and Etheridge Rivers. This property is aboriginal land. According to the Native Title Register, the traditional owners of this land are the Ewamian People. The Curr’s named their run “Abingdon Downs” after the famous Benedictine Abbey founded in 675.

The Ewamian People and their ancestors came to North Queensland long before the Saxons built Abingdon Abbey in Berkshire.

‘Dispersal’ of aboriginal people.

Throughout this memoir, my grandfather describes ‘skirmishes’ with aboriginal people by various members of the Curr family in far north Queensland. Readers may bear in mind when reading these violent encounters that the Curr brothers, their uncles and fathers were practiced horsemen, keen bushmen and were heavily armed. The aboriginal people that they fought were (at best) armed with spears, nullas nullas, woomera and boomerangs. However the first nations people understood warfare, despite their adversaries having access to armouries, advanced technology, horse, livestock and ships capable of long sea journey’s. Ray Kerkove explains in his book “How They Fought” the pastoral affrays that were typical of colonial frontier that my ancestors were part of.

The first nations people that the early pioneers fought had defeated their northern cousins from Papua and New Guinea. The spear and woomera had defeated the bow and arrow.

Blackfellas conducted economic warfare wearing down their opponent by killing their domesticated animals, their cattle and their horses. The Curr’s were proud of their large stocks of horse and cattle. They were dismayed when these animals were taken, speared and poisoned.

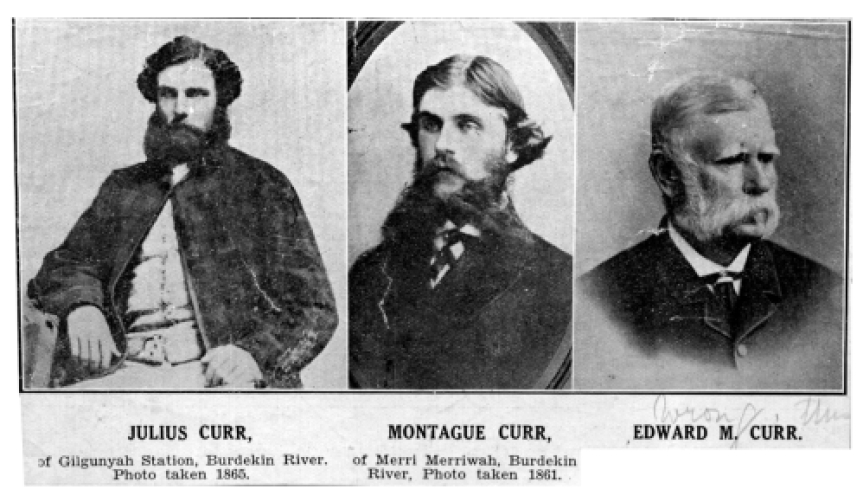

Merri Merriwah Station was the first property that the Curr brothers owned. Brothers, Marmaduke and Montague, bought Merri Merriwah on the Burdekin River near Ravenswood in 1862.

According to my Aunt Alice, her father, Marmaduke, paid £6,000 for the property. This money came from the dowry of his bride, Mary Anne Kirwan, whom he married at St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney on the 21st of January, 1862.

Later in 1862, Marmaduke went up to Bowen in North Queensland and then on to the Burdekin River where he ‘took up country‘ and stocked it with 400 head of mixed cattle. His brother, Montague Curr, was in partnership with him at the time, and their brand was CB2.

Robert Grey gave this account of an aboriginal attack on the Curr’s property Merri Merriwah circa 1864:

“The Curr’s, who had a station thirty miles farther up the river, experienced a very formidable attack, which might have easily been disastrous. Montague Curr lived with his brother, Marmaduke, and his wife. The latter, who used to milk the cows, told me his brother was out one morning after some horses, but for some unaccountable reason on this particular occasion he himself was late in turning out, a most exceptional occurrence. The blacks were almost at the door when the servant girl rushed in from the detached kitchen exclaiming, ‘Blacks, Blacks.’

He had barely time to seize a firearm before the leading darkies were at the door, and spears came rattling in. He and Mrs. Curr opened upon them with effect. Mrs. Curr, however, was grazed on the wrist by a passing spear. The brother returning about this time and coming to their assistance with his firearms, the blacks retreated to the river. They were followed up and did not renew the experiment of attacking Curr’s station, one of the neatest and tidiest little places to be seen anywhere, not a thing out of place, and no bones or unsightly debris lying about, as there often are on a cattle station, and on a sheep station also sometimes.” – from Reminiscences of India and North Queensland by Robert Grey London 1913.

This incident was also described in Fred Curr’s book, The Curr Family in Far North Queensland. According to Aunt Alice, Fred’s account was ‘highly romanticised and full of inaccuracies’. Fred could not have had any direct knowledge of these events because he was not yet born when they took place. Grandfather wrote:

“Our first adventure was early one morning in 1865. My father had taken his black boy Paddy and his big Tranter loading revolver and started out to look for the horses. Having no paddock at this time, the horses had strayed away some three miles up the Burdekin River.

My father had been gone some little time, and my uncle Montague was just going to the yard to milk the cow. When he went outside the house he spotted about thirty wild blacks, all painted and armed with spears, nulla nullas, and boomerangs. My uncle ran into the house and snatched up a long heavy 40 bore Rigby muzzle-loading rifle, and helped my mother barricade the bedroom.

My uncle opened the door a few times to show them the muzzle of the rifle, but the blacks took no notice. They then ransacked the other rooms and also robbed the kitchen and store which were separate from the main house. Finding they could not get in through the barricade into where my mother and uncle were, they decided to burn us out. The house was covered with a thatch roof, so they put fire sticks into it. As there was a heavy dew that morning the thatch did not burn too well.

While they were trying to get it to burn, the horses that my father had gone after came galloping home as horses will do on a cold morning. The blacks, thinking it was Inspector Fitzgerald and his black troopers, lost no time in disappearing into the scrub and the river. A little while afterwards my father and Paddy arrived. The blacks had taken all the powder with them, in fact everything they could lay their hands on.

It appears that some days before this event my father had given Paddy a half-pound red canister of powder. The boy had stuck this tin of powder into the thatch of the house, and the blacks had not seen it, so it was all we had. However there was enough to load two old Brown Bess Carbines, the long Rigby rifle, and the double-barrel shot gun.

My father’s Tranter revolver was already loaded, so he took Paddy, and leaving uncle Montague to look after my mother, he tracked the blacks to where they were camped, galloping into the camp and firing a few shots. The charge was so sudden, and with the noise of the firearms, the blacks left in a great hurry leaving heaps of spears, boomerangs, nulla nullas and fishing nets.

My father took a lot of these weapons home, and I remember seeing them hung about the house for many years afterwards. My father told me that it took fourteen horse loads to bring all the stolen goods back to the station. He also told me that he followed the blacks by leaves from two books, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and “Dombey and Son”.

After this episode, the Curr family were extremely careful about keeping their firearms in good order and handy to reach, with plenty of ammunition ready in pouches. My uncle Montague was wounded just above the eye by one of the spears.” – Curr Family in Far North Queensland 1862 – 1925 by Frederick Carlton Curr.

Montague Curr

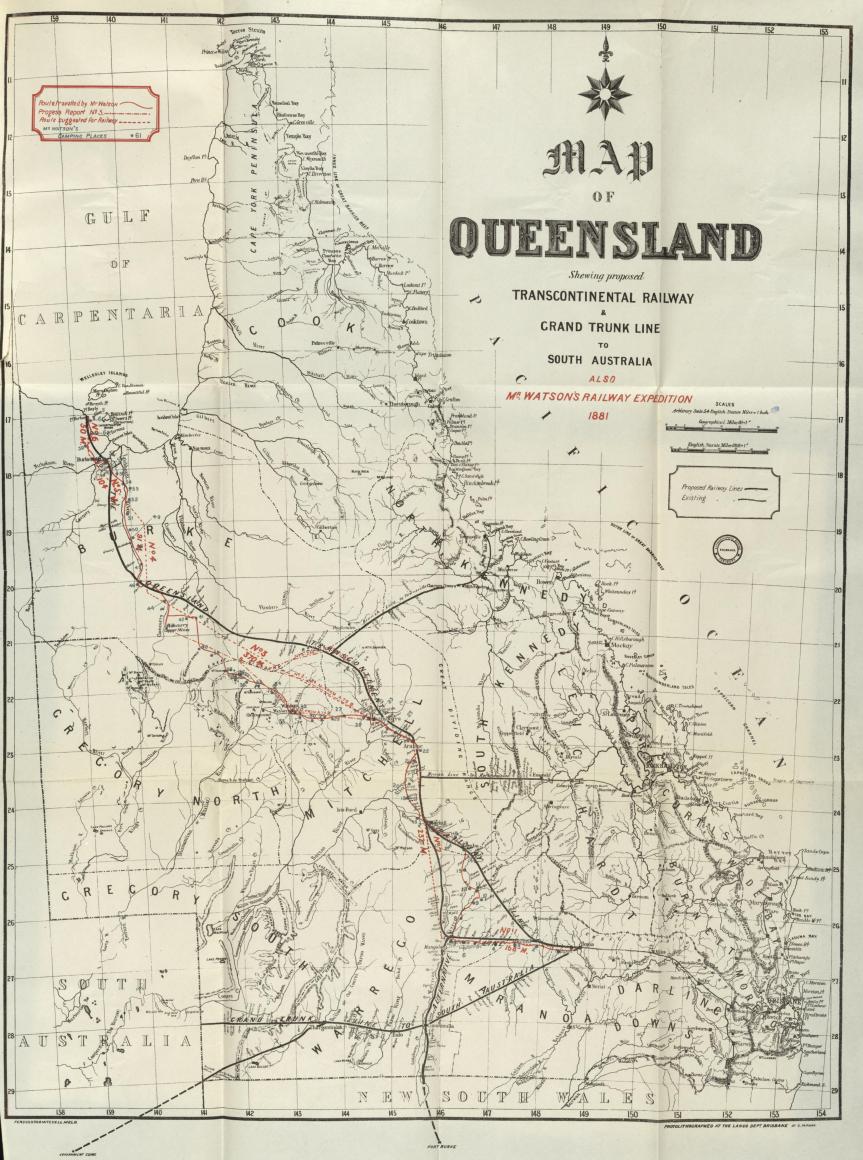

The most serious encounter for my family during the ‘contact wars’ (or perhaps they should be called ‘homeland wars‘ because the traditional owners were defending their own land) was where my grandfather’s uncle, Montague Curr (b. 1837), participated in the massacre of five aboriginal people. I am indebted to my brother, John Curr, who researched the murders described below. I also have consulted Queensland transcontinental railway: field notes and reports by railway engineer and surveyor, Robert Watson, written in 1881; and, based on his testimony, I have come to similar conclusions as by brother, John.

These shocking events occurred on Montague Curr’s property “Kamileroi” (variously spelt) in the Gulf. The Gamilaraay people, also rendered Kamilaroi, originally came from NSW. They form one of the four largest indigenous nations in Australia. As a result of a split in the tribe, some migrated to North Queensland and this may be the reason Montague Curr’s property was called “Kamileroi”.

Robert Watson, a surveyor for a northern railway describes the murders in his field notes:

Tuesday, April 19, 1881

“We came through some splendid country all the way to Kerr’s Station, Camilroy (sic), about twenty miles to-clay, fine undulating plains, lightly-timbered, and most luxuriously grassed.

“Very few creeks or water courses; those that there are well defined; only one creek of considerable size, about five miles from camp. This we crossed at its Junction with the Liechhardt (sic); in fact, we crossed it in the river, or rather rounded its mouth. We saw a lot of cattle, all well to do, sleek and happy. We passed a lot of pretty lagoons, but they will soon be dry. The river, wherever we saw it, was very beautiful, and the country very fine. When we stopped for dinner as I was under the impression that we were close to the station (Camilroy).

“I afterwards found we had fully five miles to travel. We found Mr. Curr at home, and I stopped with him during the remainder of the afternoon.”

Murder at ‘Kamileroi‘ Station

Robert Watson then describes the conversation he had with Montague Curr about his participation in the murders of five aboriginal people.

“Referring to the unfortunate stockman (Turner) recently murdered by the blacks, Mr. Curr told me that the stockman and a black boy were hunting for stray cattle. They came upon a black’s trail which they followed to their camp.

Then, they drove away the black men and took possession of the gins with whom they remained in camp. Presently the stockman fell asleep. One of the gins stole his revolver and gave the signal to the blacks who came around, put a spear through both his thighs pinning him to the earth and then beating out his brains with nullas.

Then they cleared out.

This is the boy’s version but he did not report the murder for four days. It seems the stockman had been thrashing him for some days and it is thought he may have had his “revenge”.

Mr Curr told me that he and others had pursued the blacks and shot five and that the police were coming to give them a further dressing as that was the only thing they understand.

It seems hard to steal a man’s gin and child and shoot him when he objects but I believe there is no help for it but a speedy ostensible annihilation.

The conduct of many of the whites towards the blacks is simply disgraceful.

The name of Brodie’s Station is Lorraine. It is about sixty miles above Floraville, and on the Leichardt River. They were exceedingly hospitable, and we had all our meals with them. This is Camp 49.”

Finally, Fred Curr had this to say about his uncle Montague:

“The blacks appeared to be afraid of my uncle. He was six feet one inch tall, and very strongly built. He had a long beard down to his belt, of which he was very proud, and the day before the blacks attacked the station he had shaved his head clean, so he must have appeared very uncanny. Undoubtedly this all helped to scare the blacks away until the horses came galloping home and saved our lives.” – Curr Family in Far North Queensland 1862 – 1925 by Frederick Carlton Curr.

Guilty as charged

These direct testimonies are shocking, but also they are typical of how settlers dealt with aboriginal people both in the Gulf and elsewhere in Australia. Despite denials by right-wing warriors during the History Wars the facts can’t be in dispute. Previous generations of the Curr family were coy about their direct involvement in ‘aboriginal dispersal’ which is code for murder. An important aspect of truth & reconciliation is truth telling within our own families.

Historians Raymond Evans and Robert Orsted-Jensen conclude, by cautious assessment, that roughly 66,680 people were killed and a similar number wounded on the Queensland colonial frontier from the 1820’s to Federation. [Pale Death … around our footprints springs: Assessing the Violent Mortality on the Queensland Frontier from State and Private Exterminatory Practices by Raymond Evans and Robert Orsted-Jensen]. The five murders committed by Montague Curr should be added to that grizzly list.

Discovery of Gold

The Curr family owned ‘Abingdon’ from the 1860s till 1913. If I recall correctly ‘Abingdon’ was sold for what they paid for it. My grandfather claimed that the period just before WWI was the nadir of the pioneering family pastoralists. Fred may have put the extensive Vestey family interests during this period on another level. The early pastoralists benefited from cheap aboriginal labour and later, stolen wages.

My grandfather Fred thought of himself as a pioneer. He claimed this was no longer possible in Australia after 1913. He later took himself and my father and uncles off to British East Africa. I still regard him as being a wealthy man. A little of that wealth came to my mother after my father, Joe Curr, died at the age of 50. We were all still quite young. Mum in her early forties struggled for some years to pay off Dad’s debts and the mortgage on our house. At least we had a roof over our heads and Mum had a job (several actually).

All that glitters …

I first read about Montague and Marmaduke’s role in the cover-up of gold discovery in the Charters Towers Museum in 1980.

However there are conflicting accounts. D.C. Roderick states in his memoir:

“… Montague Curr is accredited with the first find of gold in the Ravenswood area; while mustering in the Elphinstone Creek area he found a ‘show’ of gold in his pannikin when drinking at the Creek…”

The Curr brothers (were) interested in land and cattle and subsequently made their way to Townsville to purchase large areas of land adjacent to the new town subsequently to become Aitkenvale.

[As a brief aside I find it incomprehensible that Queensland’s largest northern city should be named after the most notorious slave trader in our history, Robert Towns. That his statue still stands, revered to this day, is a shocking reminder that a racist town to our north remains oblivious to Robert Towns’ legacy. That politicians, business people and church leaders can, to this day, preface their meetings with ‘We acknowledge the traditional custodians of the land … ‘ and still leave this insult unaddressed seems to be saying: ‘Yes, we acknowledge black fellas’ but then we turn and spit in their face by taking their land and naming it after a monster.]

Mr Roderick does describe how Marmaduke Curr took prospectors to one of the sites. This conflicts with family oral history passed down which claims that he and his brothers covered up this discovery because they wished to pursue their pastoral interests unhindered by a gold rush similar to that in Victoria.

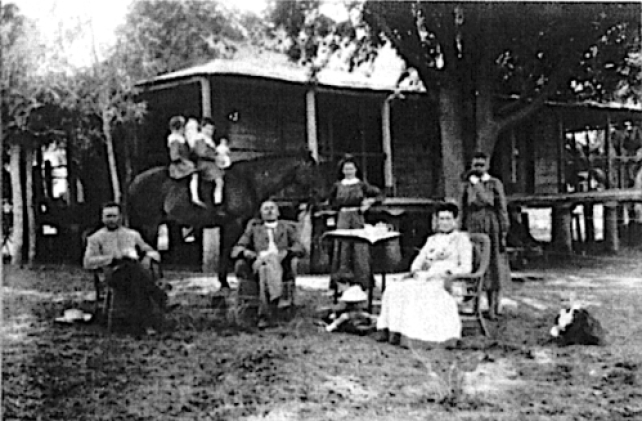

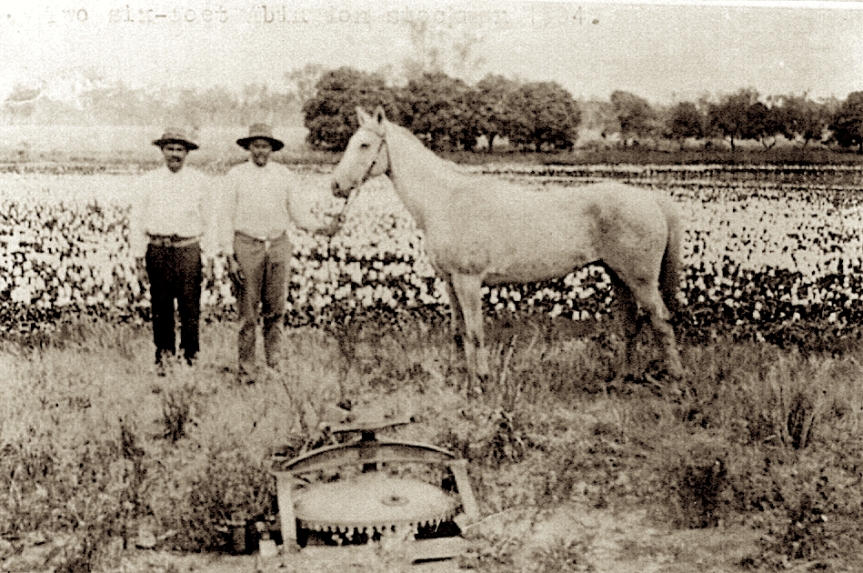

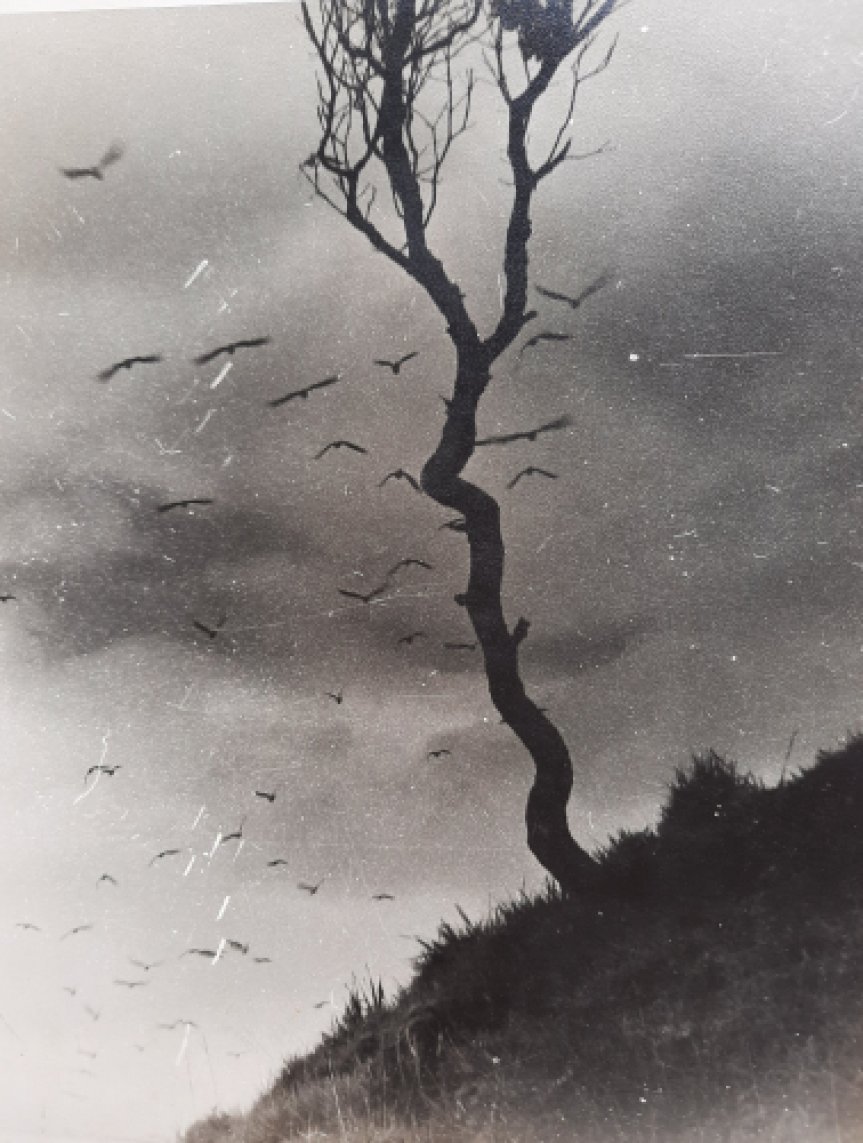

My great Aunt Alice gives her own (less romantic) version of some aspects of Fred’s account. Historians may note these Curr men were bushmen (see photo) – they were largely self-taught – so their stories are anecdotal and sometimes difficult to reconcile. Aunt Alice took care in a letter to point this out about Fred’s memoir. My cousin Eleanor included Aunt Alice’s remarks in Fred’s book.

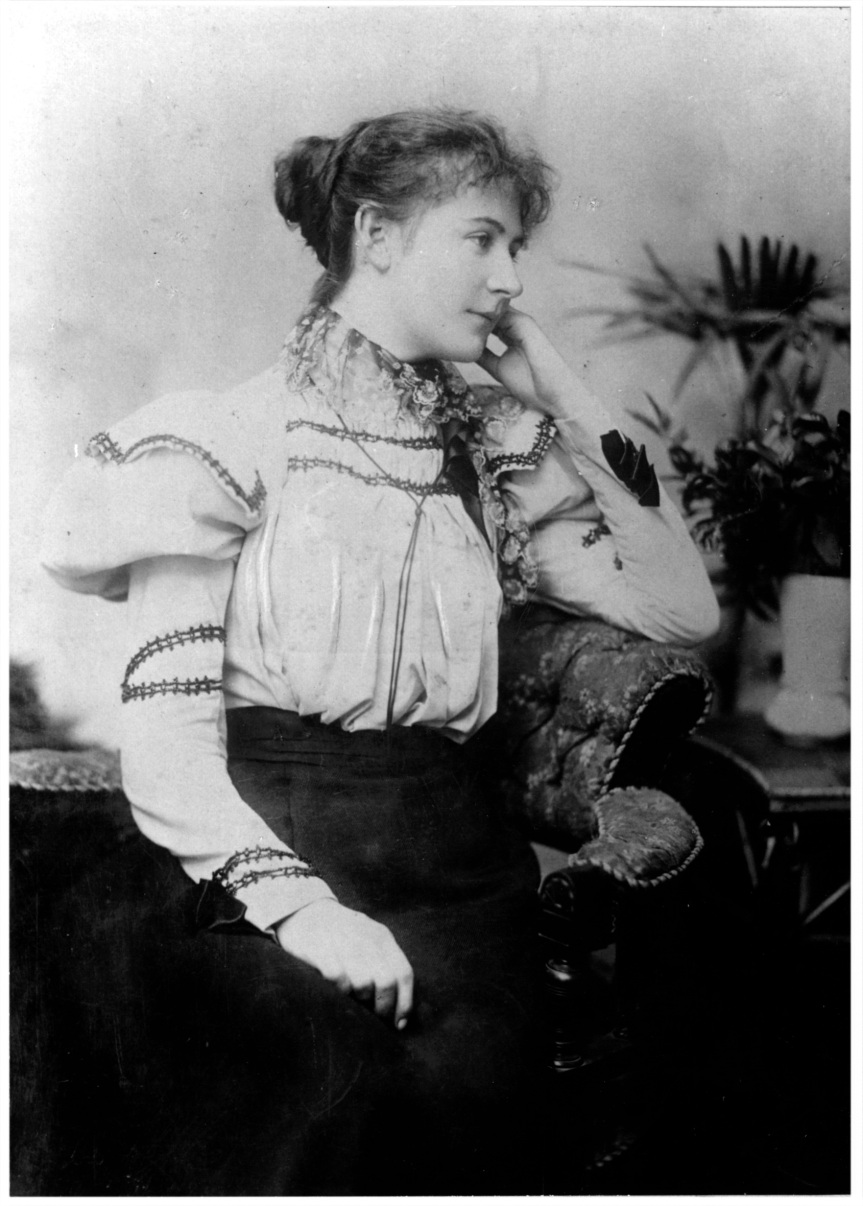

As the reader may note from the photo the ‘Curr women’ were used to greater refinement. They were keen to leave the bush and seek refuge in the coastal towns. Fred’s mother was killed, thrown from a buggy in the bush when he was young. By the way I knew Aunt Alice when she was a great age. She was an amazing woman (loupe in photo) who gave us a living human connection to another time and place, so long ago.

Neither of my great uncles benefited directly from the discovery of gold at Ravenswood, to my knowledge … they went into cattle, horses and land. My great Aunt Alice says that Marmaduke had nothing when he married Mary Anne Kirwin in 1862, and it was her patrimony that enabled Marmaduke and Montague to establish “Merri Merriwah.”

Fred Curr wrote that the Curr boys (were) without property as another impractical son, Richard, had convinced their mother Elizabeth to sell their stations. This caused their financial ruin. Fred wrote: “At this time, gold was discovered in Victoria, and we know that Marmaduke, after completing his time with the Cunninghams, went to the diggings at Ballarat. Perhaps this financed his trip to South Africa where he planned to buy a farm.“

Bushman’s ‘code of honour‘

My brother, John Carlton Alexander Curr, undertook an investigation into the murders of the five aboriginal people. His findings rely on an account by a surveyor by the name of Robert Watson. There was reference to Robert Watson’s story in Don Watson’s book “The Bush”.

My brother, John Curr wrote of Don Watson’s account: “The latter (“The Bush”) is largely a history of the influence of people, mainly Europeans on the Australian environment. In parts it drifts towards impression and poetic description. In other words, it does not present as a formal history with a strict historical method.”

My brother wanted to do his own detective work and to verify from original sources the allegation about our family member and he also wanted to ascertain whether it was Fred’s father Marmaduke or Fred’s uncle Montague against whom the allegation was made. My brother ordered up from archives the original 1881 diary of Robert Watson (no relation of Don Watson so far as we can tell).

Robert was a “surveyor” sent to explore what the local resources and geography were for the purposes of an inland railway line or transcontinental railway line. What my brother found was that it was certain that it was Montague who was the person implicated in the murders of five aboriginal persons who happened to be in the vicinity of an incident at Kamileroi station which was north of present day Mt Isa, on the Leichhardt River. There is reference to the survey party riding 5 miles from Mr Curr’s home to the junction of the Leichhardt River and Gunpowder Creek (which is at 19°14’00.0″S 139°58’44.3″E or -19.233334, 139.978975 on Google maps).

My brother relied upon Fred’s publication in the Townsville Daily Bulletin in 1931 which places the brothers in different parts of North Queensland. Fred’s father Marmaduke was at ‘Abingdon Downs‘* in the vicinity of Georgetown whereas Montague was much further to the West.

The only remaining small reservation he had about the identity of the murderer was that Robert Watson’s diary gives the account of the murders of aboriginal people slightly out of chronological order.

In the diary entry made on the day after he left ‘Mr Curr’ and in the entry when he was at a station owned by a Mr Brodie. My brother had hoped that the entry may have been a mistake and that references to Mr Curr were intended to be references to Mr Brodie. However this is unlikely because there are two separate references to Mr Curr.

The lack of contemporaneity is explained by the fact that Robert Watson may not have wanted to make the entry implicating Mr Curr in murder whilst he was in his company and on his property. It was common at that time to conceal or to be less than specific about the murder of aborigines as people knew that it was murder, hence the common reference to ”dispersal“ of aborigines which we all know meant murder. For nearly a century these despicable acts fell under the Bushman’s code of honour.

No doubt my grandfather, Fred Curr, adhered to this code so it is ironic that it was his memoir that helped bring the murders to light. Fred Curr was a member of the learned Royal Geographical Society, devoted to colonial exploration lands claimed by the British monarch.

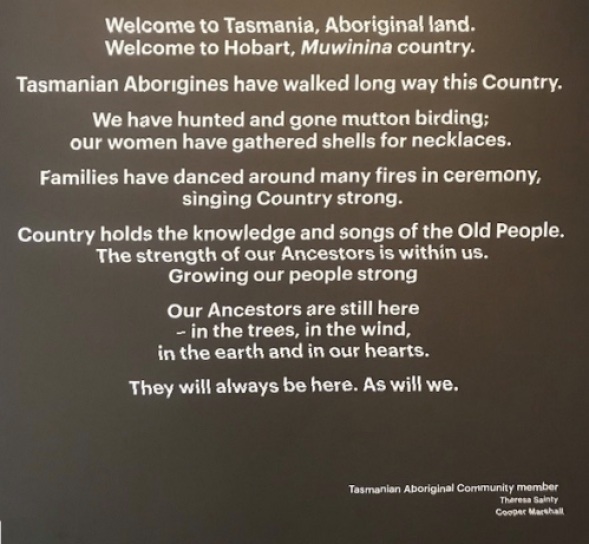

I can only wonder what the Royal Society would say to the discovery of murders covered up under a ‘code of honour’ over land never ceded. For my part I’d like to acknowledge the traditional owners of this country and the war of genocide waged against them.

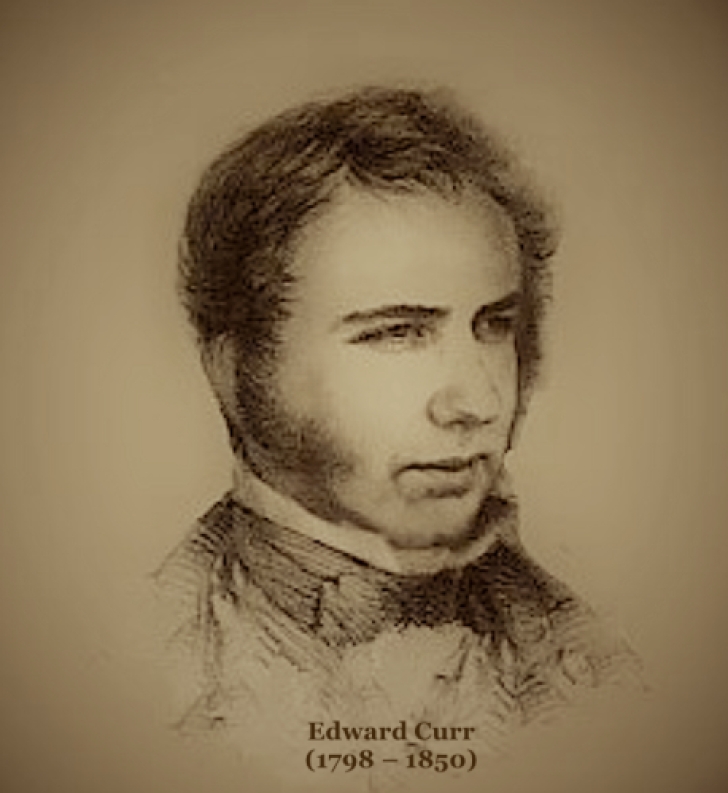

Edward Curr (1798 – 1850)

In 1824 Edward Curr senior published a book titled An Account of the colony of Van Diemen’s Land for the use of Emigrants advising British immigrants on their prospects of making a new life in the colony of Van Diemen’s Land. At the outset the Jesuit educated businessman quoted Virgil’s Aeneid in Latin:

“… quas vento accesserit oras;

Qui teneant, nam inculta videt, hominesne, feraene,

Quaerere constituit, sociisque exacta referre” – Virgil

“to seek out what regions he has reached by the wind,

to seek out who occupies the land (for he sees it is uncultivated), whether humans or wild beasts,

and to report his discoveries to his companions.”

As early as 1824, Edward Curr had identified the owners of the land but could not fully comprehend that he had stumbled upon an ancient civilisation with its own dreaming, a people that managed the land and cultivated its plants for food and medicine.

In his younger years, Curr was infused with idealism and pioneering spirit. Was he to shape a new Rome in New Holland? At his death he was referred to as the ‘father of separation‘. The colony of Port Phillip was separated from the colony of Botany Bay. By the 1850s Australia’s federated structure had begun taking shape.

Ignoring the reality of whole nations that preceded them, of which the Yorta Yorta was one example, fledgling colonies set up in Van Diemen’s land, Port Phillip, Botany Bay, Moreton Bay were to become the states of Tasmania, Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland.

Edward Curr became a magistrate in the North West of the colony of Van Diemen’s Land as well as manager of the VDL lands.

Before and during the black (the Australian) war commenced by Governor Arthur, Edward Curr offered a bottle of gin (alcohol) for the heads of aboriginal people. To my eternal shame, one of my ancestors (Edward Curr) was involved in a massacre at Cape Grimm. He not only offered bottles of gin. As a magistrate in the far North West he turned a blind eye to at least one massacre at Cape Grim. Lieutenant-Governor Arthur declared martial law on 1 November 1828 allowing roving parties to shoot or capture Aborigines for resettlement. Curr wrote to his bosses in London (he was manager of the VDL Company Lands in the N.W.) that he had offered gin as a reward for scalps of aboriginal people. Also it did not stop Curr from attempting to rationalise the massacre at Cape Grimm:

“Now I have no doubt whatever that our men were fully impressed with the idea that the natives were there only for the purpose of surrounding and attacking them, and with that idea it would be madness for them to wait until the natives shewed their designs by making it too late for one man to escape. I considered these things at the time for I had thought of investigating the case, but I saw first that there was a strong presumption that our men were right, second if wrong it was impossible to convict them, and thirdly that the mere enquiry would induce every man to leave Cape Grim.” [See Inward Despatch No.1. Curr to Directors. 2 January 1828. AOT VDL 5/1.}

Keith Windshuttle (an historian and apologist for the genocide) used the same flawed reasoning as Curr to cast doubt on the severity of the bloodshed. The shepherds were attacked as a result of earlier attempts by them to steal aboriginal women. Windshuttle also claimed that the weapons the shepherds used could not have killed so many people. I don’t know about the shepherds but my ancestors were always heavily armed and capable shots. You only have to see Fred Curr’s armoury (pictured below) to appreciate how well armed they were. Fred Curr’s armoury at “Abingdon” at Corinda contained numerous musket, shotgun, carbine, cutlass, sword, pistol. Please note also the collection of boomerang, woomera, and nulla nulla captured from first nations people.

The shepherds called the hill where the massacre occurred Victory Hill.

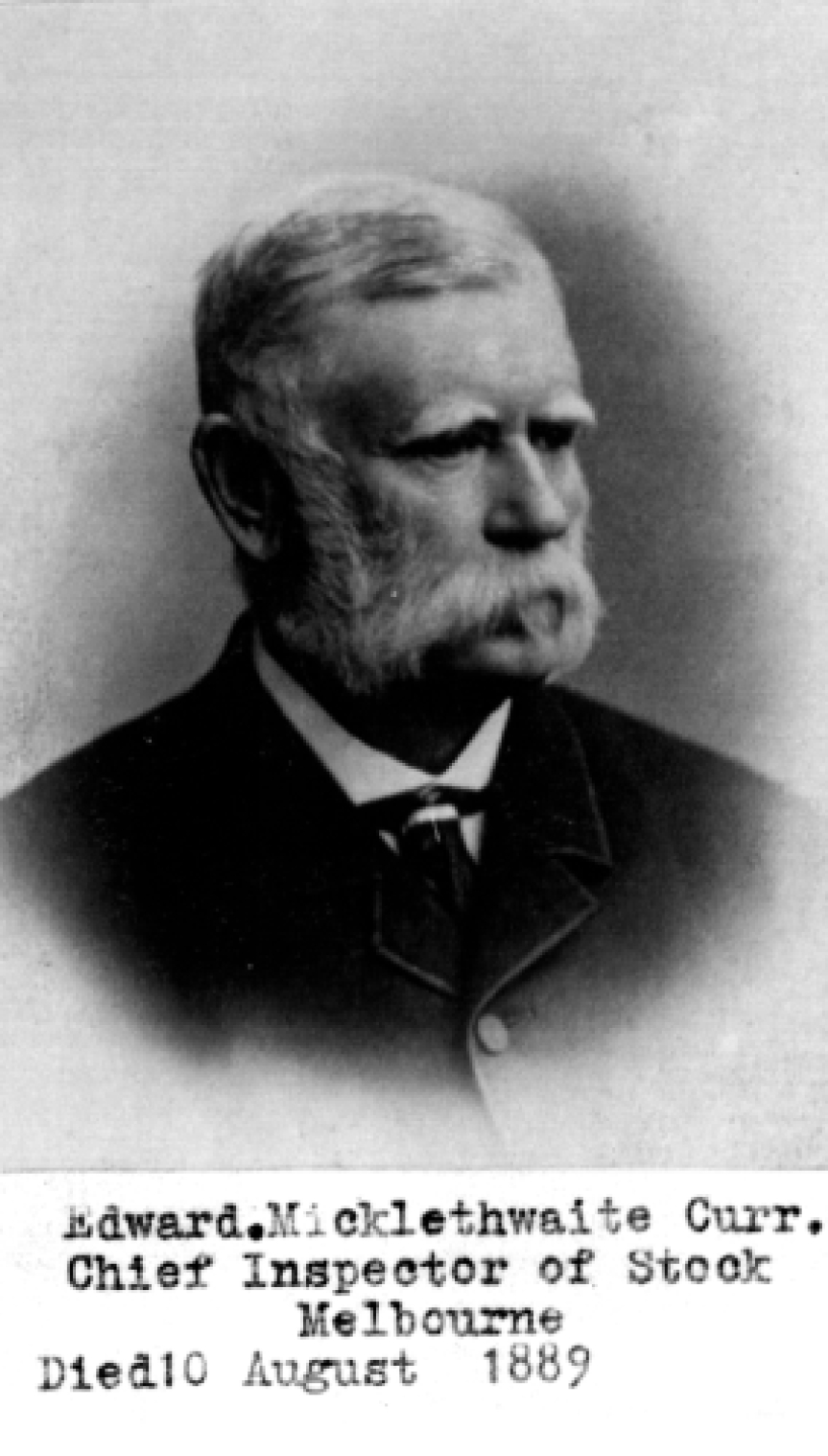

‘Edward M Curr and the tide of history’

Curr’s oldest son Edward Micklethwaite Curr wrote a number of books including Squatting in Victoria and The Australian Race (in 4 volumes). These became the cornerstone of the High Court’s justification of dispossession of the Yorta Yorta people from their country near the junction of the Murray and Goulburn Rivers in Northern Victoria and southern New South Wales.

He describes the tribe which he calls the Bangerang as savages and in one instance complains about murders committed by an aboriginal man he refers to as Jack Jumbuk-man. Yet he makes no mention of how his brother, Montague, murdered five aborginal people at Kamileroi station in the Gulf nor of how his father turned a blind eye to the massacre of 30 aboriginal people at Cape Grim by four Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDLC) workers in his employ.

Samuel Furphy in his book, Edward M Curr and the tide of history, describes Edward Curr’s role in the dispossession of tribes where he set up his runs. There were explicit statements of contact wars in Van Diemen’s land by Edward Curr and his son, Edward. There was talk of the need for armed struggle to dispossess aboriginal people of their land. The pioneering Curr’s were fearful that aboriginal nations would combine to drive settlers out of the country. Nowhere in the many volumes of the Curr’s books, dairies, or correspondence with the Van Diemen’s Land company and with the governors of the colonies was there a single reference to terra nullius. This was because they were squatting right beside the original inhabitants often using them for cheap labour and to rely on them for better knowledge of country. That myth of legal rights to land, rivers, seas, mines and pasture was propaganda invented later. Sadly, by federation in 1901, both courts and governors in Australia had built their own narrative separate from the reality of an ancient dreamtime.

Curr’s ‘cartwheels turned up tubers’

Just as the myth of terra nullius was long exposed by the various Curr’s writings and photographs, so too was the common belief that aboriginal people were hunters and gatherers. The journals of early settlers like Edward Curr, James Kirby, George Augustus Robinson, Mitchell and Sturt disclosed that there were yam, tuber and grain farmers among aboriginal nations.

Edward Micklethwaite Curr testifies to this in his book Recollections of Squatting in Victoria. The young man on his venture up the Goulburn River describes aboriginal agriculture and how his ‘cartwheels turned up tubers’. Curr recognised that it was his sheep that destroyed native yam crops cultivated by tribes living along the Murray River. Sadly the High Court gave no weight to this part of the historical record in its decision over the Yorta Yorta claim for land rights. No one who reads the historical novel, Secret River, written by Kate Grenville in 2005 or watches the series of the same name on ABC TV could fail to recognise that settlers on the Hawkesbury River stole yam farms from first nations people and deprived them of the very means of their existence.

In the words of William Augustus Robinson in his report to the colonial office in London, Aboriginal people had ‘nowhere left to stand‘ thus provoking this ‘whispering in our hearts’. Bruce Pascoe says, as an aboriginal man, he came across these discoveries in early settlers journals. ‘Other people read them before me, but looking at it from an aboriginal perspective, professors did not see any significance to aboriginal civilisation’ says Pascoe. Young people between 5 and 25 are interested in it, says Bruce Pascoe.

I commend Furphy’s book ‘Edward M Curr and the tide of history’ to readers interested in how Australia was setup as a settler state. Two hundred and fifty years after the landing of James Cook at Botany Bay, Australian people still carry the burden of that historic fiction. I include an excerpt of the book below.

“When the High Court of Australia rejected the final appeal in the Yorta Yorta native title case in December 2002, a headline in The Age announced: ‘Claim sunk by pen of a swordsman’. [Fergus Shiel, ‘Claim sunk by pen of a swordsman’, The Age, 13 December 2002.]

“The man in question was Edward M. Curr (1820-1889), who was certainly fond of fencing in his youth, but is better known as the author of Recollections of Squatting in Victoria (1883), an engaging account of his early life as a pastoralist on the Goulburn and Murray rivers. In 1841 Curr was among the first squatters to occupy land belonging to ancestors of the Yorta Yorta people, described by Curr as ‘the Bangerang Tribe’.

“His nostalgic memoir is one of very few written accounts of Indigenous life in the early years of the pastoral invasion of northern Victoria. The apparent failure of Yorta Yorta people to maintain traditions identifiable with those that Curr had described was a key reason for the defeat of their native title claim.

“Born in Hobart in 1820, Curr was the first son of English-Catholic immigrant parents. His father was an influential businessman and politician, who played a prominent role in the early colonial affairs of Van Diemen’s Land and the Port Phillip District of New South Wales (later Victoria). Curr himself was educated in England and France before managing his family’s squatting runs for a decade.

“His pastoral endeavours were highly successful and the dispossession of the Indigenous owners was swift. He later experienced financial failure but recovered to forge a successful career as a government official in Victoria, rising to the senior position of Chief Inspector of Stock. From 1875 he was an influential member of the Board for the Protection of Aborigines during a highly controversial period; he doggedly pursued the closure of the Coranderrk Aboriginal reserve near Healesville, publicly displaying a profound paternalism and disregard for the wishes of the Indigenous people concerned.

‘Edward M Curr and the tide of history’ by Samuel Furphy

Montague Curr was guilty of murder most foul by killing five (5) aboriginal people at Kamileroi Station in 1881, but his father and brother performed more insidious crimes against humanity through their deeds, connivance and writings.

Always was, always will be.

Ian Curr

27 Dec 2020

Notes

Thanks must go to my brother, John Curr, who did such good detective work to find out that one of our relatives, Montague Curr, in the company of others, was responsible for the murders at Kamilleroi Station. We both recommend that these murders should be included in the Colonial Frontiers Massacre map 1788-1930.

My mother was a great story teller and much of the knowledge I have about Fred Curr comes from mum. I thank my mother, Bettina, and my siblings, Pam, John and Georgina for the many hours spent discussing this history of dispossession by our forebears.

Finally, thanks to my cousin, Eleanor Freeman, whose endeavours delivered the original text of the memoir by Fred Curr that gives first hand accounts of the frontier war that was waged in North Queensland in the latter part of the 19th century.

Any errors in this digital version of that history are, of course, my own.

References

Queensland transcontinental railway: field notes and reports, with map showing positions of various camps – Watson, Robert, active 1882-1883 nla.obj-116096067

Reminiscences of India and North Queensland, 1857-1912 by Robert Grey https://www.textqueensland.com.au/item/book/a424ad40d00f39499e21ce92fa7dd5c7

Foreward by Eleanor Freeman

“Uncle Fred”, my great uncle, began his account of the Curr family in 1916 and made several additions until 1925.

As far as I know he made two copies, one of which he gave to his niece, Mary Douglas, my aunt, who allowed me to make a copy before returning it to Fred’s grandson John Curr.

This account is basically as Uncle Fred wrote it. I have changed it only to correct certain dates and occasions where he contradicted himself, and I have divided it into chapters and sections. The dates of birth, death and marriage have been verified at the state libraries of Queensland, New South Wales and Tasmania.

Aunt Alice, our beloved great aunt, and Fred’s sister, who I knew well, spoke constantly about her parents and “Abingdon”, and often said that Fred’s account was romanticised and full of inaccuracies. He had every right to reminisce and romanticise his experiences. He was, however, incorrect about the attack on “Merri Merriwah” when he said that he was a baby at the time. Both Aunt Alice and his Aunt Florence, Sister Elizabeth, have verified that the attack occurred before he was born. (Appendix G).

I first met Uncle Fred in 1945 when my mother and I travelled to Brisbane from “Buckie”, Moree, where we had spent the war years.

I had been born after my father had left for the war, and we were en route to Sydney where I was about to meet him for the first time following his return from Changi. Uncle Fred offered me his large hand and took me into the air raid shelter in his garden at “Abingdon”, Corinda, then proudly showed me his collection of firearms – his pride and joy.

He valued that collection highly.

That day in 1945 was one of sad recollections. Uncle Fred’s third son, Frank, a Pilot Officer, had disappeared without trace during a flight from Townsville to Thursday Island on the 24th September 1944. Frank had had an outstanding career in the Air Force. He had been awarded the DFM and Bar for his bravery during flights over Germany and Italy, and had recently been awarded the Pathfinder’s Badge in 1944. In addition to the Air Force, Uncle Fred had organised special private searches for him, all to no avail, and he was heartbroken. My Uncle Julius, Charlie’s only son, had been killed by a land mine while walking back to camp after the Battle of El Alamein in 1942, and the following year my grandmother, Mary Theresa Curr, died at Moree. It was a time of great re-adjustment for everyone.

I saw Uncle Fred on subsequent trips to Brisbane, and have fond memories of the tenderness of this shy old bushman towards his late brother’s grandchild. He died in 1953, on my birthday, 4th February, just thirty-seven days short of his 88th birthday.

There has been some confusion among family members thinking that Marmaduke was the son of Edward Micklethwaite Curr. Uncle Fred inferred this and Aunt Alice later corrected him. (Appendix H). Marmaduke was, of course, the younger brother of Edward Micklethwaite. Edward Micklethwaite, the first child of Edward and Elizabeth {Micklethwaite} Curr, was born in 1820 then left Tasmania in 1829 with his brothers William and Richard to be educated in England. In 1833 they were joined by their brothers Charles and Walter and their sisters Agnes and Augusta, so when Marmaduke was born in 1835 his seven oldest siblings were overseas. Edward, William and Richard first met their four-year-old brother when they returned to “Highfield” in 1839. Edward Micklethwaite then spent ten years, 1840 to 1850, managing his father’s stations during which time Marmaduke and his younger brothers Montague and Julius were presumably educated in Melbourne

(Port Phillip). Marmaduke’s sister Florence, in her letter to Uncle Fred, illustrates how little she knew her brother. (Appendix G). There appears to be no record of the younger boys being sent to England. Following the death of their father Edward in 1850, Edward Micklethwaite, along with his brothers Charles and Walter, returned to Europe (William had already died), and the fifteen-year-old Marmaduke went to live with his sister and brother-in-law, Agnes and Hastings Cunningham at “Mt. Emu”, to learn station management. It was about this time, between 1851 and 1854, while his brothers were away, that Richard, the unpractical third son, encouraged his mother Elizabeth to sell all the stations that Edward had bequeathed to his sons. This left the Curr boys without property and caused their financial ruin. Also at this time, gold was discovered in Victoria, and we know that Marmaduke, after completing his time with the Cunninghams, went to the diggings at Ballarat. Perhaps this financed his trip to South Africa where he planned to buy a farm. Aunt Alice tells us that Marmaduke had nothing when he married Mary Anne in 1862, and it was her patrimony that enabled Marmaduke and Montague to establish “Merri Merriwah.” (Appendix H). The early lives of the older children of Edward Curr seem to have been more glamorous than those of the younger ones.

__oOo__

Certainly after their father’s death, the Curr brothers followed diverse paths. Charles died in Ireland in 1858 leaving one son who soon died and a daughter. Richard travelled to France where he married, then returned to live in Melbourne. He had no children. We know that Walter also travelled to Europe in 1851 then to the East, and served as a volunteer in the Indian Mutiny. Later he joined his brothers Julius and Montague growing cotton in Fiji. It was while visiting “Abingdon” in 1880 that he died of Gulf Fever. We know nothing of Arthur who also died young and unmarried. Julius and Montague left Fiji to join Marmaduke and his family, then retired to Melbourne where they died.

In spite of age differences and vast geographical barriers, the children of Edward and Elizabeth remained in contact and took a great interest in each other. The letters and anecdotes bear witness to this. Marmaduke’s wife Mary Anne spent the first year of her marriage with her mother-in-law in Melbourne while Marmaduke and Montague were establishing the station at “Merri Merriwah”. During that time she established close bonds with the family, hence the concern expressed by various members when they heard about the attack on “Merri Merriwah”. Edward Micklethwaite Curr’s account of the family, written in 1877, was dictated to his daughter Mabel and copies were made by hand and dispersed to all the family. Aunt Alice told me she made her beautifully handwritten copy when, aged fifteen, her mother took her to Melbourne to meet her cousins. This copy became the first part of Uncle Fred’s book. It is perhaps extraordinary, that, of Edward Curr’s nine sons, (excluding Charles), only Edward Micklethwaite and Marmaduke had families.

Aunt Alice was disappointed that Uncle Fred made so little mention of their mother. It was Mary Anne’s £6,000 inheritance that established Marmaduke on the land after their marriage in 1862, and interestingly the probate evaluation of “Abingdon” after his death in 1898 was for the same amount.

Marmaduke and Mary Anne’s children did not enjoy the comfortable childhood and educational opportunities of their parents. Walter and the girls were sent to school in Brisbane, but Fred and Charles completed their education at “Abingdon” with tutors while helping their father run the station. They worked hard. They were all indomitable pioneers, and seemed to see their lives as an adventure in the wilderness. The long months of isolation, particularly during the wet season, encouraged them to read avidly and direct their minds towards the outside world. As soon as they could, they travelled overseas to visit the places they had so often read about. The loneliness of their situation created strong ties which have continued down the generations. We, the grandchildren of Fred, Charles and Walter were lucky to have known Aunt Alice for a large part of our early lives, and so we heard her stories first hand. We loved her dearly.

Uncle Fred’s travels lived up to all his expectations, and “the dreams of a lifetime were realised.” This 46-year-old man who had spent all his life in the Australian bush now marvelled equally at the Egyptian antiquities and the Renaissance art and sculpture of Italy, the latter he described as “some wonderful work done with a chisel.” By 1925 he had disposed of all his landholdings, but continued to make many trips back to the Gulf. He took a great interest in the development of the beef industry, and before his death was made a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society for his work in exploring and opening up the Gulf Country.

I am grateful to my aunt, Mary Douglas, for allowing me to copy Uncle Fred’s story, and to both Bettina and Robert Curr for their anecdotes and assistance. Also to Jill Ryan, Charlie’s great grand-daughter, for her assistance in preparing my manuscript for printing.

Eleanor E. Freeman. Sydney, October 1989

Part I

EDWARD MICKLETHWAITE CURR’S MEMORANDA

1 . Origins

Of my great grandfather on my father’s side I know little. He lived in Northumberland, in which county he was viewer of coal mines. He brought up his son, John Curr, as a civil engineer. My grandfather, who was a well-educated man, became steward to the Duke of Norfolk when he was about twenty-one years of age. He took up his residence at Sheffield and at Belle-View House in the neighbourhood of that town. He lived for many years, and died in 1823. He was a man of considerable ability, self-reliant, original, and hard-headed. At least such is my impression from what I have heard my relatives say concerning him. As I have said, he managed the estate and coal mines of the Duke of Norfolk from his twenty-first year until his death. At that time, coal was brought from the mouth of the pit for a certain distance in vehicles which ran on wooden rails, and it occurred to my grandfather that a great saving would result from the substitution of iron rails which up to that time had been unknown.

Pondering on this subject, he wrote to his father telling him that it was his determination to substitute the wooden tramway with iron rails.

To this the old Northumbrian replied that what his son contemplated was an innovation which in no wise met with his approval, ending his short letter with the words “if you put down iron rails, Jack, I curse you, and here is my hand on it”. On the opposite side of the page my great grandfather laid his stalwart hand, around the edges of which he drew his pen. His father’s anger was due to the fact that he owned forests and supplied timber to the mines.

In view of this denunciation my grandfather abstained from taking further steps in respect of his iron rails until sometime afterwards, when, mentioning this matter to a priest who was dining with him, he learnt that, notwithstanding what his father might think, it was his duty to act as seemed to him best for the interests of the Duke of Norfolk. He then laid down the rails which created such a feeling amongst the colliery population that they threatened to take his life, so he hid himself in a wood for three days until the ferment had subsided. I have seen my grandfather referred to in the life of one of the Stevensons and elsewhere.

I am very glad to say that my grandfather was a very exemplary and sterling Catholic. As an instance of his frame of mind in connection with religion, I may relate that, when he was a young man and somewhat a beau, it was the fashion to wear a queue. This appendage required a hairdresser to arrange it before the wearer could appear in public.

My grandfather was of course a punctual attendant at Mass on Sundays.

It is related that on one occasion the hairdresser arrived so late as to render his compliance with the Sunday obligation impossible.

He reached the church long after the service had begun, and, on his return home said to his attendant “I will never be late for Mass again on account of my queue, so take the scissors and cut it off”. His attendant did as he was required. Few now-a-days would estimate correctly the sacrifice of self which this act implied. It almost amounted to what a Hindu would call “loss of caste”.

Shortly before he died he entrusted a certain Pere Duchesne with thirty thousand pounds to invest for him in the French Funds. The poor priest, with little knowledge of business, took upon himself the responsibility of investing the whole sum in some mercantile bubble which he thought would be more profitable to my grandfather than the funds. The bubble, however, presently burst, and absolutely nothing was saved from the wreck. The poor priest returned to England to lay the sad news before my grandfather who, however, had just died. He went to the executors, and after stating what had occurred said “gentlemen, except the clothes in which I am dressed I have nothing to offer by way of restitution for the loss which I have occasioned except this silk pocket handkerchief.”

Years afterwards when I was a young man, this handkerchief was in the possession of my mother who said to me “Eddie, my boy, this handkerchief is all that your grandfather’s family got for thirty thousand pounds – God willed it should be so.”

My grandfather married a Miss (Hannah) Wilson, I believe of the family of the “Fountain Wilsons.” I knew her very well in the summer of 1831 and the winter of 1833. She was an old lady, benevolent, strict, and starch. She kept a good house in Sheffield. When I knew her she was blind in one eye, and so deaf that she could only hear with a trumpet. When there with the Miss Ellisons (typo?), (Mr. Ellison [Wilson?], I believe, succeeded my grandfather as steward to the Duke of Norfolk in 1831), we used to amuse ourselves with ringing all the bells in the house. The old lady, fancying she heard a noise, was unable to make out what it was. She was a very religious woman, and towards the end of her life removed from Sheffield to York to be near her daughter Harriet who was a nun at York Bar Convent. The poor old lady was always very kind to me, took care not to flatter my vanity, and died in about her 98th year.

My grandfather was buried in Sheffield, and when a boy I often saw on the wall of the Sheffield church a marble tablet bearing a commemorative inscription of him. This church was pulled down sometime about the year 1845.

My grandparents had three sons and, I think, four daughters.

His eldest son was called John. He lived at Norwich where he was an importer of tobacco, enjoyed a considerable income, and kept his carriage and hunters. Unlike the rest of the family he was a little man, but a good horseman. He painted well, and had studied engineering in which he was well read. In 1833, my father being then in England, my uncle John came to Sheffield where my father had taken a house for a few months, and passed some time with us. My father having just come from Van Diemen’s Land, conversation naturally turned a good deal on colonial ways and doings, the result of which was that my uncle determined to give up his business, and, in the sunny climes of the south, become a grower of the weed of which he had hitherto been an importer. From this step my father endeavoured to dissuade him.

Uncle John, however, who had married beneath him, leaving the younger members of his family in England to be educated, sailed with his wife and elder children for Van Diemen’s Land. Eventually he left for New South Wales and tried unsuccessfully to grow tobacco on a farm near Wollongong . He eventually went to Sydney and again became a tobacco merchant. I think it was in 1849, after having elaborated a scheme by which steamers could do their voyages with only half the coal then used, that he went to England for the purpose of getting his views brought into use by shipowners. In this he failed. I saw him in Melbourne the day after my father’s death in 1850. He told me that when in England he accidentally saw an advertisement signed by a person by the name of Curr. This individual, it appears, was a rich man resident in Aberdeen. He was entirely without family or indeed relatives of any sort to whom to bequeath his wealth, and it was in hopes of finding an heir that he had penned his advertisement. After an exchange of letters, my uncle accepted his invitation to visit him, but on talking matters over, my uncle, who was well up on family history, and the old gentleman were unable to establish any relationship. I may here notice that about 1864 a young gentleman named Curr called on me in Melbourne. He was from Scotland, and I think the name of his native town was Abroath. Uncle John died at his farm near Wollongong I believe about 1857. Of his children, I know little. His two eldest sons, John and Charles were with me at Stonyhurst College Lancashire. John edited a newspaper at Wollongong, published a book or pamphlet called ‘The Learned Donkies” which I have not seen, went home to England to see about some property in about the year 1870, and while there died suddenly of heart disease.

Charles was a writer on the Press. In 1852 or thereabouts he was sent home from Melbourne by the proprietors of the Argus newspaper with a salary of £800 a year as a special reporter. In 1850 he had been engaged to be married, but the lady jilted him and he took to the bottle. It was about 1858 that, being engaged on a newspaper, he went to bed one night, drunk as was often the case, and was found in the morning dead in his bed. He appeared to have passed away in a state of unconsciousness and without a struggle. I paid the editor of the newspaper a portion of his burial expenses. His brother Laurence Curr was originally educated for a priest. He left college, however, and came to Tasmania. I met him in Sydney in 1858. He was at the office of the Protestant Bishop, and I have heard he is since dead. He had, I believe, a brother called Henry, who I have heard is a priest. As far as I know, my uncle John had only three daughters. Mary Anne, whom I knew in London, a charming girl, took the veil in Belguim. Therese, who gave up her religion, married a Mr. Gaunt in Tasmania. The third sister’s name I do not know. I have heard that she is a protestant and married to a squatter in Queensland.

My brother Montague has met her.

My grandfather’s second son Joseph was ten years older than my father and embraced the priesthood. He was well off, an excellent man, published a book connected with the sacraments and the duties of catholics entitled “Familiar Instructions in the Faith and Morality of the Catholic Church adapted to the use of both children and adults”.

This work reached at least three editions. He was a tall man, handsome, stern looking and intellectual. He owned a considerable collection of paintings, was chaplain to Bishop Penswick, and used often to see us at Stonyhurst. He was a very exemplary man, always gave us good advice and money to spend. If I remember right, he died somewhere about 1848 of a disease caught while attending the sick.

Of my father’s sisters I know little, having never seen more than two of them. The eldest, Elizabeth, married a Mr. Furniss, who, after the death of my grandfather, resided at Belle-View. She was thrown out of her carriage and killed, leaving behind her five children. Her eldest child, Albert Furniss, who died in 1874, emigrated to Canada where he married a French Canadian called Priscilla Arnoldi. He did well and lived in great state. Her second son, the Reverend John Furniss, published largely on subjects connected with religion. Another son, Bernard, was brought up as a doctor and died when about twenty three years of age. Helen married Henry Smith, has no children, and resides near Durham. Julia became Mrs King and died leaving one son who was an officer in the Lancers and died in London. My second aunt, Harriet, meeting I believe with a disappointment in love, took the veil and lived in the convent at York where she became superioress for about fourty five years. She took a cold bath every morning. She bore the reputation of being a very holy and clever woman. The third daughter Mary Anne married a Monsieur Beauvoisin, lived in Manchester, and had two children Henry and Mary Anne. I believe another of my father’s sisters, called Theresa, also took the veil and died early. I know nothing more which need be mentioned concerning my father’s family.

2 . Edward Curr

My grandfather’s third son, my father, was named Edward Curr. He was born on the 1st July 1798 at Belle-View House near Sheffield. When about five years of age, he was sent to school at Sedgely Park where the master used to ill treat him rather more than he did the other boys. When annoyed, he was accustomed to say as he flourished his cane “Curr, you hound, I’ll cut your liver out”. Having taken the first steps on the flowery path of learning at Sedgely, my father was transferred to Ampleforth College and subsequently to Ushaw College near Durham. He was well up in the classics and a good mathematician. I think he finished his education when between sixteen and seventeen years of age.

Archbishop Polding and Cardinal Wiseman were at Ushaw College with him. After leaving college he was placed in a merchant’s office at Liverpool where he remained for two years. My grandfather then gave him his choice of any business or profession which he might elect to follow. He, however, had got an idea that the colonies presented more favourable openings for young men than the overcrowded societies of the old country, and in accordance with this view, he sailed for Pernambuco in South America, taking with him a few books in Portuguese. He passed several months in Brazil, acquired the habit of speaking Portuguese, made some long trips inland, and saw a good deal of the country. As, however, the state and customs of the country were not to his liking, he returned home determined to look further before he made his choice. Whilst in Brazil he met Charles Waterton, the celebrated naturalist. He returned to England in 1818 or 1819 and married my mother, Miss Elizabeth Micklethwaite, from whom he received a considerable sum of money. The marriage ceremony was performed at Belle-View House on the 30th June 1819 by the Reverend Richard Rimmer, a catholic priest, and was repeated the day after in the Protestant church in Sheffield by the Reverend Matthew Preston. This was necessary as, at that time, a marriage by a catholic priest in England had no force in law.

My mother’s family have resided at Ardsley Hall near Barnsley, Yorkshire, I am told, for many generations. My maternal grandfather, Benjamin Micklethwaite, was born at the paternal residence, but in what year I am not aware. He was educated in Germany, and on his return from that country made his appearance at Ardsley in the disguise of a recruiting sergeant, in which, however, he was found out by his mother.

I have heard many stories connected with him from which it appears that he was a dashing horseman, a good shot, a practical joker, and a rather hard drinking squire. On the 16th May 1795 he married Miss Sarah Lister, a native of Laughton, by whom he had one child, my mother Elizabeth, who was born on the 21st May 1798. She was a posthumous child, for my grandfather died at Grenoside near Sheffield on the 19th January 1798. This daughter, Elizabeth, was of course my mother. She was noted in youth for a dignified and kindly manner and great personal beauty. My maternal grandmother, after having remained a widow until 1806, married Francis Mayor by whom she had two daughters, Hannah (Mrs Bramhill), and Mary (Mrs Colley). Mrs Colley had a son called Frank who I believe is still alive at Sheffield, about fourty three years of age, and wealthy. Concerning the Bramhills, I noticed in a Melbourne newspaper of November 1876 that one of them failed at Sheffield for sixty thousand pounds.

*

After my father’s marriage he purchased merchandise in connection with a partner whose name was John Raine. A notice of their dissolution of partnership on 4th September 1820 appeared in more than one number of the Hobart Town Gazette. In October 1819, the two left England and reached Hobart Town, Van Diemen’s Land, on the ship “Claudine”, in February 1820. There my father, with great trouble, disposed of his merchandise and his partner who in some manner had misconducted himself.

I, the writer, was my father’s eldest child, and was born at Hobart Town on the 25th December 1820. My brother, William Talbot Curr, was also born at Hobart Town on the 7th March 1822. My father was made a member of the Legislative Council by Colonel Sorell, the Governor of Van Diemen’s Land. According to the regulation then in force, my father was entitled to a government grant of an acre of land for every one pound sterling, or its value in merchandise brought by him into the country, so he might have selected and obtained grants for two or three thousand acres of land. However he had not found Van Diemen’s Land to his liking, and had decided on returning to England, and contented himself with exercising his right to the amount of one thousand acres. Having sold his merchandise he also sold his land which was, I believe, on what is called the Cross Marsh, at twelve shillings an acre. Then with his wife and family he embarked on board the brig “Deveron” and sailed for England on the 6th of June 1823.

On the 22nd of that month my brother Richard was born off the coast of New Zealand. I have heard he was a delicate little fellow, and was wrapped in cotton. He was called “Shungy” after a well known New Zealand Chief at that time.

On the voyage home which lasted over six months, my father wrote a little work entitled “An Account of the Colony of Van Diemen’s Land” which was printed in London in 1824. About this time a company had been formed in London with a view to colonisation in Van Diemen’s Land. Amongst its members were many rich and influential people and members of both houses of parliament. Its capital was one million sterling, and the Imperial Legislature had made it a grant of about 350,000 acres. This company took offices at number 55 Old Bond Street London, and invited Colonel Sorell, recent Lieutenant Governor of Van Diemen’s Land, to attend a meeting of its Board of Directors for the purpose of obtaining from him information concerning the objects which the company had been established to effect. The Colonel, who appears not to have had the faintest idea of anything connected with country pursuits, answered their questions as well as he could and informed them that there was a gentleman in London well qualified to give them the information they needed. This was my father, who was introduced to them by ex-governor Sorell. The Board of Directors offered my father the office of Secretary at eight hundred pounds a year which he accepted temporarily. Shortly afterwards he was induced to take the management of their affairs in Van Diemen’s Land under the title of “Agent of the Van Diemen’s Land Company”. This undertaking was considered at that time to be the most important of anything of the sort south of the Equator.

Late in 1826 my father proceeded with his family to Van Diemen’s Land in the ship “Cape Packet”, touching at Madeira and Rio de Janeiro en route. It was a pleasant circumstance connected with the terrible voyages of those days that we always touched at some ports on our way. None of my recollections of life are half so enchanting as those which refer to foreign countries in which I landed in my early childhood. Shortly after his arrival in Van Diemen’s Land, full explorations having been made, my father took up Circular Head, Woolnorth, Emu Bay, Surrey and Hampshire Hills as well as other holdings for the Company.

In the middle of 1829 I and my brothers William and Richard were sent home to Stonyhurst College, Lancashire, for our education.

In 1833 my father again visited England on leave of absence.

The Directors of the Company being so well pleased with his management that they presented him with eight hundred pounds to pay for the trip. Before leaving England on this occasion he left at Stonyhurst with his three sons already there my brothers Charles and Walter. He also placed at school at Preston, Lancashire, my sisters Agnes and Augusta. He now had five sons and two daughters at school in England. He reached Van Diemen’s Land again in 1835 after an absence of eighteen or twenty months.

From the beginning my father was a large shareholder in the Company. Though much attached to Circular Head, which had its singular bluff, beautiful bays, pleasant beaches, unsurpassed climate, and those green fields which had been as it were his own creation and had grown into as lovely a place perhaps as any in the world, he gave up his position there in 1841. He betook himself to Port Phillip which district offered to his young and numerous family advantages incomparably greater than any presented by Van Diemen’s Land. He parted with the Company, whose land he had selected, and whose affairs he had managed for so many years, on the best terms.

That a man frequently fails to give effect to his plans was remarkably instanced in the case of my father, who, from the day of his arrival in Port Phillip, seemed almost to forget that he had any family, as he busied himself heart and soul in politics, almost to the exclusion of every other consideration. At that time, what is now the Colony of Victoria (then known as Port Phillip), was governed by New South Wales of which it formed a portion, and the revenue raised in Port Phillip was expended in New South Wales. To bring this evil to an end and obtain a separate government from the mother country was of course the question of questions for Port Phillip. To obtain this object my father constantly laboured for seven years; in fact until it was known that separation had been finally determined on by the Imperial Government.

The money which he expended keeping house in town, with the object of procuring separation, which he considered his particular mission, had it been expended in the purchase of property of any kind, would have been worth to his family ten years after his death a quarter of a million in money. This business completed, he let his town house and went to live on his station. After residing there for about twelve months, he let his station with a view to returning to politics. Shortly after, he died in Melbourne on the 16th November 1850 in his fifty second year, on the very day the news of separation reached Port Phillip. My father was followed to the grave by the head of the government in Victoria and the principal inhabitants of Melbourne. The newspapers, in recording the fact, spoke of him by the title which he had long borne, “The Father of Separation”.

As regards personal appearance, my father was a big man, measuring six feet and an inch in height, and weighing seventeen stone at forty years of age. He had a fine head, large and square, a massive jaw and abstracted looking grey eye. In his ideas he was original, firm in his resolves, and with an understanding I should think of as first class.

I never saw him in company or conversation, even on the most trifling occasions, when anything but the first place was given up to him. Habitually, and unknown to himself, he imposed his will on others, and I have always thought that people treasured up a resentment against what I may call a state of momentary vasselage to which they found themselves reduced in his presence. It would, I think, be difficult to find anyone more respected by those who knew him, or more respectable than my father. He was a man of marked ability, extended sympathies, unimpeachable character, distinguished presence, the head of a patriotic movement then afoot in the colony, and of what were then large pecuniary resources. One of the minor matters in which he shone was as host when seated at the head of his own dinner table. In this he was ably seconded by my mother.

Both my parents were singularly free from affectation of any sort.

In summing up, I may add that my father was decidedly unpopular with the gentry, a fact which I can only account for on the supposition that an imperial manner, which was as natural to him as his skin, was not relished, and though five and twenty years have passed since his death, it has never been forgiven. He left his family well off. To his sons he bequeathed his stations. They were let at the time of his death to my brother Richard and a Mr Hodson. At that time occurred the discovery of gold. My brothers Charles, Walter and myself being in the old countries, my brother Richard and my mother sold the stations, which were yielding two thousand a year, for eleven thousand. This ruined my father’s sons. For my father’s freehold properties which were left to his daughters, thirty thousand pounds were refused at one time for St.Heliers, and twenty two for a house in Collins Street nearly opposite the Bank of Australasia.

My father’s nine sons were myself, William Talbot, Richard Taylor, Charles, Walter, Arthur, Marmaduke, Julius, and Montague. His six daughters were Agnes (Mrs Hastings Cunningham), Augusta (Mrs Henry Field Gurner), Juliana, Elizabeth (Mrs Daniel Pennefather), Florence (a Sister of Mercy), and Geraldine (Mrs Charles Warburton Carr). Of these, William, Charles, Arthur and Juliana are dead. Charles, most lately deceased, died in Ireland in December 1858. He was the only one married of those who are dead. He left behind him a son since dead and a daughter Florence. His widow later married a Dr. Wood with whom she and Florence reside at present near Pontefract in Yorkshire.

3. Edward Micklethwaite Curr

As I have already said, I was born in my father’s house at Hobart Town on Christmas Day 1820. In 1823 I went home with my parents, returning with them to Van Diemen’s Land in 1826. In 1829 I was sent to England with my brothers William and Richard to be educated at Stonyhurst College, Lancashire. We made the voyage in charge of my father’s butler, poor old Jimmy Scully. Scully had been a marine in His Majesty’s Navy, was present and wounded in several of Nelson’s battles, and had also been a convict, yet long knowledge of his character enabled my father to confide in him as an excellent servant and a man of integrity. We went round Cape Horn in the ship “Lady Rowena” which had the bulwarks carried away in a storm. Our cargo, which was wool, caught fire which the crew, however, succeded in extinguishing. On the voyage we were also chased by a pirate. She was a small vessel with many hands, and the wind being very light, she succeeded between daylight and four o’clock in getting within a mile of us. Our four cannons were loaded and arms distributed to the crew, for it was well known that death awaited us on capture. At four o’clock a strong wind fortunately sprung up so that we escaped, and a few days afterwards entered the harbour of Rio de Janeiro where we remained a fortnight to refit. During this interval I remember a British Cruiser captured and brought into Rio the vessel which we had so narrowly escaped.

We arrived in England after a voyage of six months and twelve days, and were sent to Stonyhurst College in Lancashire, I think in the month of October 1829. Whilst at College I was always backward, employing my time, as soon as I had learnt to write, in writing reviews of works and also novels, poems, sermons and so forth. In August 1837 William, Richard and I were removed from Stonyhurst to St. Edmonds College at Douai in the north of France. We stayed there about nine months, being then boarded out at a village in the neighbourhood called Quincy, the object being the acquisition of the French language. Whilst in France we became excellent swordsmen. In November 1838 we returned to England, and in January 1839 sailed in the “William Bryan” for Circular Head where we arrived in the month of May. In August 1839 I paid my first visit to Port Phillip. Shortly after, I passed some months with Dr. Milligan, the Company’s Superintendent, at the Surrey Hills. I left the Hills to manage a small establishment belonging to the Company at Emu Bay, at which place I passed five months. In December 1840 my father bought a small station in Port Phillip called “Wolfscrag” which he sent me to manage. On this occasion I reached Melbourne on the 9th of February 1841.

Shortly afterwards I deserted “Wolfscrag” and took the sheep to country in the neighbourhood of the junction of the rivers Goulburn and Murray where I took up a station, “Tongala”, for my father.

I managed this station for ten years. In 1846 my father gave me a thousand ewes and my brother five hundred with which we went into partnership. To graze these, I took up a small run adjoining my father’s which was known as “Corop”, or more correctly “Gargarro”. Shortly after my father had given us these sheep, poor William died, leaving me his heir. In 1850, having sold some of my sheep, I let the 4,000 which remained for three years at three hundred and twenty pounds per annum, and on the 15th February 1851 sailed for England on the ship “Stevonheath”, my brothers Charles and Walter being in the same ship. On arriving in London I shook hands with my brothers and went to Cadiz where I passed eight months. I then went to Seville where I also passed eight months. By this time I had learned to speak Spanish with tolerable facility. Leaving Seville, I went by land to Grenada and thence to Almeria where I took a ship to Marseilles, went up the Rhone to Lyons, and thence to Geneva. On leaving Geneva I passed over the Simplon into Italy, reaching Venice by way of Milan. From Venice I went to Florence, Rome and Naples, and finally to Brindisi from where I sailed to Corfu in an eight ton boat laden with garlic. From Corfu I proceeded by steamer to Patras, and rode along the Gulf of Lepanto in company with my guide to Corinth and thence to Athens. I spent some time at Athens then sailed to Constantinople, where, after seeing the sights I went to Beyroot. There I engaged a dragoman and proceeded into the Lebanon visiting Zahali, Damascus, the Cedars, and Tripoli among others. Having had a misunderstanding with my dragoman, I discharged him on my return to Beirut where I passed some weeks. Having picked up a little Arabic, I continued my travels alone by Sidon, Tyre, Acre, and Jaffa to Jerusalem, at which city I arrived about the 16th October 1852. I remained three weeks, in Jerusalem at the Casa Nova, visiting the Dead Sea, San Saba, and Bethlehem. Then I proceeded to Gaza, and after a few days delay to Cairo which I left for Alexandria on the 20th November. From Alexandria I proceeded via Malta to Gibraltar which I reached on the 24th December 1852. I returned to Seville where I remained until 17th January 1853 when I proceeded by way of Madrid and Bayonne to Paris and then to London. Subsequently I passed some time in Dublin, Paris, Brussels and London.

Whilst I was away on my travels, gold was discovered in Victoria, and my brother Richard sold my run “Gargarro” for four thousand pounds. On the 31st January 1854 I married Miss Margaret Vaughan with whom I have since lived in the greatest happiness. She has been invariably the best of wives, and on looking around I cannot help noticing how few of my friends have been favoured as myself in this particular. Finding in my experience that interference on the part of the husband in little domestic concerns frequently leads to discontent on the part of the wife, I made it my rule from the beginning that my wife should be supreme mistress in my house. To this course, and to her innate good sense and sweetness of temper I attribute the peace and contentment which have been visible in our home.

If at any time I have taken any part in our domestic concerns, it has merely been occasionally to tender my advice. Miss Vaughan, who I met in Dublin, was of a family long resident in Kildare. Her father, having run through his paternal inheritance, obtained a situation in a mercantile house in Liverpool, in which city he and his wife died.

In accordance with the ideas of those times, he made a point of not engaging in business, as he might have done in Dublin, as such a course would have been considered derogatory to the family dignity. After my marriage I returned to Port Phillip, which I reached on 21st August 1854, and in September I left for Auckland with my wife, it being my intention to buy sheep and land there. This however I was unable to do. I remained in New Zealand until the 24th January 1856. Whilst there I brought from New South Wales to New Zealand two cargoes of 100 horses, each out of which I cleared about eleven hundred pounds. I also published some letters on the land question which were afterwards printed by the editor in pamphlet form. On leaving New Zealand we went to a station which I bought in the Burnett district in Queensland.

The station consisted of two blocks of country called “Gobongo” and “Tincola” which we reached on the 6th of March 1856. There were depasturing on it 3,000 head of cattle for which, if I remember right, I paid two pounds five shillings a head. In the course of twelve months I sent cattle over to Melbourne in two drafts, having sold the run without any cattle for two thousand pounds. I think it was in January 1858 that I bought a station on the Lachlan River called “Euaba” in company with my brothers Richard and Julius. We put a thousand head of cattle on it and were ruined whilst there in consequence chiefly of the dry weather. We left “Euaba” somewhere in June 1861. Having about three hundred and fifty pounds in hand and no more, I invested three hundred in horses which I took to New Zealand, clearing three hundred by the transaction. In November 1862 I was appointed Inspector of Sheep with a salary of three hundred and fifty pounds a year which a few months after was raised to five hundred a year. In 1863 I published a book entitled “Pure Saddle Horses”. On the 17th May 1864 I was appointed Chief Inspector of Sheep. The object of the Act under which I was appointed was the eradication of scab from amongst the flocks of the Colony. This object was accomplished on the 9th of June 1876 as appears in the Government Gazette of that date. On the 16th of January 1873 I was appointed Chief Inspector of Stock, my salary being raised to seven hundred a year. These appointments I still hold. One of my children, Wilfred, died at “Euaba” on the 24th of August 1860. The others, Edward, Constance, Mabel, Ella, Justin, Hubert, and Ernest are still alive. Edward, the eldest, was educated in part at the Jesuit College at Namur and in part at the College of Mondragone near Rome. I have been as fortunate in respect of my children as of my wife. They have always been good and dutiful, and I trust they will be happy and pray for me when I am gone. Suffering from sore eyes, I dictated the foregoing pages to my daughter Mabel in whose handwriting they are.

Signed Edward Micklethwaite Curr, 7th January 1877.

Part II

19TH CENTURY

4 . Marmaduke

Edward Curr’s son Marmaduke was born at Highfield House, Circular Head, Tasmania, in February 1835. He was the eleventh of the fifteen children of Edward Curr and his wife Elizabeth, and the seventh of their nine sons. When quite young he went to live with his brother-in-law, Hastings Cunningham, of “Mt. Emu” Station near Chepston, Victoria, to learn station management. In 1852, after the discovery of gold, he left Mt. Emu, and went

digging at Ballarat where he knew many of the characters of Rolf Bolderwood’s book “Robbery Under Arms”. After leaving Ballarat, he went to Cape Town, South Africa, with a view to settling there and going into cattle raising. However he did not like the country and returned to Australia in 1861. He married Mary Anne Kirwan at St. Mary’s Cathedral , Sydney, on the 21st of January 1862.

Later in 1862 he went up to Bowen in North Queensland and then on to the Burdekin River where he took up country and stocked it with four hundred head of mixed cattle. His brother, Montague Curr, was in partnership with him at the time, and their brand was CB2. In 1872 Marmaduke dissolved the partnership with Montague who took up and stocked “Cardigan” Station, and later in 1875 took up and stocked “Kamileroi” Station on the Leichhardt River. He remained there a few years, then sold out and retired from bush life, later travelling to Japan. He bred a splendid herd of cattle on “Kamileroi”. He was a wonderful bushman, day or night he could not go wrong. He remained a bachelor and died in Melbourne.

In 1878 Marmaduke sent seven hundred head of mixed cattle out to “Donor’s Hill” in the Gulf Country in charge of his brother Julius Curr. A few months afterwards Marmaduke went out to “Donor’s Hill” and was very disgusted with the country, so he went looking for more suitable land which he discovered on the Einasleigh River in 1878. In 1879 he took up and stocked “Abingdon Downs”. His brother Julius helped him with droving the cattle from “Donor’s Hill” to “Abingdon”, arriving there in August 1879. The same year Marmaduke sent 400 mixed cattle and 100 horses from his “Gilgunyah” station on the Burdekin River to “Abingdon”, then sold “Gilgunyah” to Symes and Buckland from Charters Towers. He then removed his wife and family of three sons and three daughters to “Abingdon”, arriving there on November 22nd 1879. Marmaduke’s brother Julius stayed with the family until 1883, and after his departure Marmaduke continued to develop the station with his three sons Frederick, Charles, and Walter, and many were the hardships they all endured. He died in January 1898 at the age of 63.

5. Merri Merriwah and Gilgunyah