On 23 May 2014, Magistrate Costello found Wayne Wharton and Hamish Chitts ‘not guilty’ of ‘obstruct police’. In April 2013 Brisbane City Council officers asked police to assist them in putting out the sacred fire in Musgrave Park. Police arrested Wharton and Chitts for obstruct police while defending the sacred fire.

However the magistrate also found Wayne Wharton guilty of ‘Wilful Damage‘ to a Brisbane City Council sign that had inscribed on it the words: ‘aboriginal land’. The magistrate fined Wayne Wharton $400 (with 16 days in jail in lieu). He said he would refer the fine to SPER [State Penalties Enforcement Registry].

In his judgement the magistrate said that he did not accept the defence argument that the sacred fire was part of aboriginal religious practice. He ruled that no right exists to have the sacred fire in the park without the permission of Brisbane City Council:

Lest there be any doubt, I wish to make it abundantly clear that there must be compliance with Brisbane City Council by-laws and regulations with respect to any conduct whether or not the DOGIT [Deed of Grant-in-Trust] area exists. That is to say, the conduct complained of by the Council cannot be repeated without prior approval being first obtained from the Council.

Magistrate Costello did not accept that aboriginal people had a right to defend the sacred fire (or that it was ‘sacred’). He did not accept that police and council actions were unlawful. In his written judgment the magistrate claimed:

On 29 July 1999, a DOGIT was sealed in respect of land described as Lot 3/SP110538 County of Stanley Parish of South Brisbane consisting of a total area of 9,051 square metres granted in fee simple to the Brisbane City Council “to hold the land in trust for Aboriginal and for no other purposes whatsoever”.

Interests in land were granted to or for the benefit of Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders under the Land Act 1962 (repealed) and are now granted under the Land Act 1994, and other legislation? During my consideration of this matter, it became clear to me that the area of the existing DOGIT as agreed to by the prosecution and the defendants may not necessarily be correct.

Costello further claimed:

Assuming the DOGIT area still exists, the Council needs to turn its mind to its specific identification and in that event, I would suggest that once identified, boundaries need to be clearly marked.

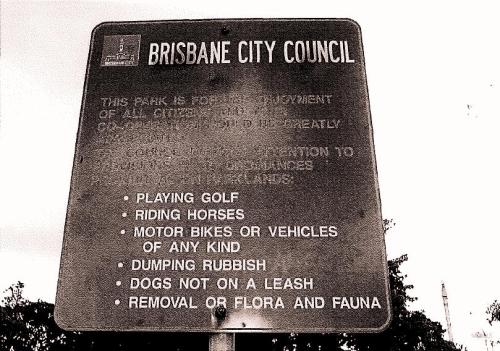

In any event, it seems to me that the current sign is not specific enough and needs to also refer to the activities complained of.

Yet the magistrate did find both defendants “not guilty of ‘obstruct police’.

The magistrate also found that the DOGIT lease designated for an aboriginal purpose would still be subject to the laws of the State.

Earlier in the trial the Magistrate questioned police prosecutor Treloar about the meaning of ‘aboriginal purpose’ as referred to in the DOGIT:

“BENCH: But- but if that’s the case, what-what meaning do I put on the words Aboriginal purposes?

SGT TRELOAR: Well, your Honour that-that’s really an argument that is beyond the forum, in my submission, of this court. There is – there is —

BENCH: But it’s a defence raised. How can it be beyond the forum?

SGT TRELOAR: It’s – Its – It’s a – a defence raised without any real understanding though.

BENCH: But yeah. Well, that might be so, but what do you say about it?

SGT TRELOAR: I- I say that the land is the council’s, that the council is -has the authority in relation to that land —“

In the end the Magistrate found that:

The conclusion I have reached is that any DOGIT area “for Aboriginal and for no other purpose whatsoever” would be subject to compliance with existing legislation namely the Brisbane City Council by-laws and regulations.

The struggle over the sacred fire continues in the courts with three other defendants fighting cases about the same issues.

When asked by the magistrate for submission on penalty Wayne Wharton said that he did not accept the finding of guilty on the wilful damage charge because:

“This country was occupied by force. Under my law (your finding) means nothing here. I submit nothing.”

Conclusion

No matter how many times the question of the sacred fire is taken to court, the act of lighting the fire is never addressed by the magistrates or the police. But rather the authorities dance around the key issue that the fire is central to aboriginal and many other cultures. It is part of my culture and I am not an aboriginal person. Police used charges of obstruct against Wharton and Chitts as the basis of repressing the ceremony of the sacred fire.

In his decision the magistrate used the time worn strategy of trying to drive a wedge between the Native title claimants (the Turrubal people) and the tent embassy. What the magistrate fails to understand in his judgement is that one of the Turrubal claimants came down to the sacred fire specifically to support the tent embassy.

If the DOGIT area is specified as aboriginal land then how can the police be acting lawfully when they come to put out the fire inside the DOGIT area? Nowhere in the Police Powers and Responsibilities Legislation does it say that obstruct police is to prevent the practice of aboriginal ceremony and culture.

Ian Curr

23 May 2014

Reference: Costello decision in R vs Wharton and Chitts

hello john,

regarding yr comment:

Yet in Qld, the LNP is implementing the Cape York Institute’s proposals to privatise DOGIT communal lands. Noel Pearson (Cape York Institute) and Andrew Cripps (Minister for Natural Resources and Mines) share the same dream … wholesale land reform that takes away country from blackfellas and places it in the hands of a few … see Aboriginal Land: more ‘bucket loads of extinguishment’

The High Court has made a blanket extinguishment of Aboriginal customary law on the basis that it contravenes the racial discrimination act. This is the basis of the Walker vs NSW case that the magistrate refers to and is routinely used to dismiss any case related to customary law and sovereignty..

Until recently, there has been no statute, state or federal, that in any way acknowledges Aboriginal customary law, consequently there has been no available challenge to the High court’s blanket extinguishment.

However the recent Federal Act of recognition is a statute that, in the words of the act, “acknowledges the continuing relationship of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with their traditional lands and waters.” and “acknowledges and respects the continuing cultures, languages and heritage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.”

The key word in this legislation is “continuing” – it is acknowledged to exist today.

While this act is vague and does not in any way define the nature of culture and relationship to land, the simple fact that there is something, even if it has not been defined, that still exists today means that it contradicts the high courts blanket extinguishment of all customary law.

Before the high court’s blanket extinguishment, obligations and responsibilities under customary law were accepted as fact and admissible as evidence in court. For example, Galiroy Yunipingu was charged with assault and willful damage when he smashed a photographers camera and acquitted because he had a lawful obligation to do it. This defense is no longer allowed as customary law has been criminalised. However the act of recognition puts this defense of customary law obligation back on the table as there is now, for the first time ever, a statutory basis for a high court challenge to the blanket extinguishment of customary law. … http://unlearningtheproblem.wordpress.com/