[This Paradigm Shift was broadcast on 19 October 2012 on 4ZZZ fm 102.1]

A derelict house slumps to one side

Poster peels on a bolted gate

Its faded but not forgotten

“An injury to one is an injury to all”— ‘View From A Wooden Chair’

Lachlan Hurse and Sue Monk

Contents

Intro

Song – View from a wooden chair

The Long Night

Song – La Guittara

Voices for Victory

Song – Cantombe Mullatto

Wide Awake – the rise of union solidarity

[All songs are sung by Jumping Fences – more details can be found at their website]

***

Intro

Jumping Fences – View From A Wooden Chair Lachlan Hurse and Sue Monk

It is not coincidental that Paradigm Shift address the question of the Politics of Repression (second part in the series).

There is a storm on the horizon that will affect workplaces, homes, our civil society.

The rich buggers are getting nervous. Why?

Because some profits are falling while others are mounting. Of course they will blame the workers, the ordinary people for this change — if fact they already have..

I went to the federal court this week and amidst a cacophony of lawyers wearing batman outfits, sweating and clutching their briefs, I heard federal magistrate Jarrett give building worker and seaman, Bob Carnegie, three options:

- Plead ‘Guilty’ to 53 counts of contempt of court

- Argue there is no case to answer

- Plead ‘Not Guilty’

So lets explain some of that. Firstly why ‘contempt of court’ charges?

Well, the Qld Children’s hospital building workers went on strike for 8 weeks to protect their jobs and their pay. One of those building workers told me yesterday that he went within an inch of losing his house.

So how did it come to this?

For 650 workers building the largest government construction project in Qld goin’ out on strike for 8 weeks was a major step.

let’s go back in history to the 1998 MUA dispute where CEO of Patricks stevedores sacked its entire workforce in one night with the full backing of the federal government.

ON THE 19th April 1998 union and community stood tall against the the Howard government and its corporate backers on the waterfront.Pam Curr was down at Swanston dock in Melbourne when workers, locked out by Patricks, convened ‘the longest picket line in history .. here is the story of what became known as The Long Night

***

The Long Night

The tension in the room was palpable as members of different unions spoke. It was 4pm on Friday 17th April and eighty of us were sitting in a circle in the MUA headquarters in West Melbourne. Information had been gathered from workers in different unions which backed up the belief that Kennett had delivered an ultimatum to police to clear Swanston Dock and open it up for Patricks.

The facts were gathered from union members and pieced together to reveal the plan. Members reported buses had been arranged to take a large number of police from a city railway station to the docks probably after midnight. Another union had been informed by their members that hundreds of warrants had been written up to expedite predicted mass arrests. No police from the local area around the docks were to be used in this operation. Then the barrister for the union revealed that the watch-house which was always chronically overcrowded had been magically emptied. The evidence was conclusive a move was to be made on East Swanston Dock that night.

I was there with women unionists as a community member to express support for the MUA and tell them that the community wanted to stand alongside the Wharfies. We recognised them as the frontline for workers. If the government could knock them off, we were all done for. Over 100 years of union struggle was not going to be wiped out. One of the male workers stood up and thanked me but said he did not want ‘ladies’ on the line. He felt this was men’s business to which a woman unionist responded, ‘This is workers’ business and women are workers too and want to stand up and be counted just like the rest of you.’ This finished the gender argument once and for all. The stakes were too high for division. Decisions were made fast and furious under pressure. Mobile phones interrupted with news as it came to hand.

It was agreed all unions would take turns in manning the picket. The women workers at the MUA were setting up a 24 hour phone service. They had mattresses in the office and would take turns bunking down for sleep and maintaining communication. Community Radio 3CR gave out MUA headquarters phone numbers so that any information could be forwarded quickly to where it was needed. 3CR also called up supporters to get down to the picket telling them when they were most needed. This was community radio’s finest hour – a direct link to the people. We left the meeting knowing a long night was ahead of us and that we could all be arrested by morning.

The crowd swelled steadily from 7pm down at Swanston Dock. The marshals called them to practice every half hour or so and we all learnt how to link arms and interlace our fingers so that the police would have to pry us apart one by one to break this line. We agreed that we would be arrested. We were not going to make it easy for the government. Fires were keeping people warm. Their spirits were lit from within with the resolve to win this fight. There was only one toilet just inside the gate and the line was long but practicalities had to be attended to. We knew to be locked in a paddy wagon with a full bladder would be murder.

As the night wore on the crowd grew more resolved. We were now assembled in front of the gates. The marshals on the speaker system letting us know what was happening as news came to hand. At 2am lookouts reported police getting into buses in the city. We knew the time was approaching when we would be tested. Next they were marching down to the dock. It was too dark to see much but we could make out the shadowy outlines of 400 police. Then the helicopters started buzzing us with bright search lights. Back and forth for 40 minutes. It was irritating but good humour and black jokes mitigated the intended effects which were to rattle us.

As dawn was breaking the seagulls wheeled in the rosy light. The marshals on the loudspeaker kept us informed and there we stood 3000 of us facing off 400 police, both implacable. The 7am news bulletin on the ABC informed us that many of the police had removed their badge numbers. A roar of disapproval went up from the crowd. It was too dark for us to see but the journalists were close enough to take in such details.

As light broke we began to see the police more clearly. Our legs were aching after hours of standing on the cold hard bitumen. At least the unpredictable Melbourne weather was being kind – no rain.

By eight o’clock in the morning we were exhausted. The camaraderie was strong; strangers were sharing laughs, mandarins, water, and chocolates, whatever we had. We were at a stand-off when a roar started. What a sight! Builders’ labourers marching down the road toward us. We waved and shouted and cheered them in. This put the police in a pickle. They were now sandwiched between weary but steadfast picketers and fresh building workers. Discipline held firm as we cheered the new recruits onto the picket line. Leigh Hubbard from Trades Hall led the police off the dock and they retreated to a Mexican wave and voices singing, ‘goodbye, farewell, sad to see you go.’ Like hell we were! We had won!

Tired and exhilarated we headed home to sleep leaving the picket in safe hands. This was the beginning of a remarkable period in Melbourne. Swanston Dock, which until then had been as foreign to most of us as Timbuktu, was to become as familiar as a second home over the next two weeks. Restaurants and theatres emptied as night after night Victorians gathered on the docks. On weekends country folk came down to join their city cousins bringing sausages and chops for barbecues. All the churches were represented standing in support of the wharfies. A Buddhist shrine was erected under some bushes with ‘MUA Here to Stay’ across the top. Tents sprang up to feed and tend the growing community. Young environmentalists came down from the forests and cooked community meals for the picketers. A stage was erected and singers and comedians entertained the community. This was the essence of community and it started on the long night when workers and community came out in support of a group of workers who have always been the frontline defence of the Union Movement. The government thought this would be a pushover. They never dreamt that the community would rally for the wharfies. They were proved wrong on that night and in the weeks to come as the crowds swelled every night at the Peaceful Assembly on Swanston Dock chanting the familiar refrain ‘Workers United, Will Never Be Defeated.’ – Pamela Curr, FairWear Campaign,[8] 5 April 1999

la guitarra

Voices for Victory

A Benefit Concert for Workers

at the Queensland Children’s Hospital Site

On 2 October 2012 one of the longest and most important construction industry strikes in living memory ended in victory for the workers at the Queensland Children’s Hospital site (see over for details). Many of the workers and their families continue to suffer financial hardship as a result of their involvement in this dispute. The Trade Union Defence Committee is a community organisation formed to assist these and other workers in struggle. All proceeds from our benefit concert will go directly to the QCH workers in need.

On 2 October 2012 one of the longest and most important construction industry strikes in living memory ended in victory for the workers at the Queensland Children’s Hospital site (see over for details). Many of the workers and their families continue to suffer financial hardship as a result of their involvement in this dispute. The Trade Union Defence Committee is a community organisation formed to assist these and other workers in struggle. All proceeds from our benefit concert will go directly to the QCH workers in need.

“We are not going to build a children’s hospital as industrial slaves in a modern wealthy society…”— Bob Carnegie, 22 September 2012

On 2 October 2012 construction workers at the Queensland Children’s Hospital (QCH) site returned to work victorious after a strike lasting almost eight weeks. The project’s main contractor, Abigroup, part of the massive Lend Lease empire, has signed an enterprise agreement with a subcontractors’ clause ensuring all workers performing similar roles are paid the same rate, whichever subcontractor employs them.

Without guaranteed equal pay – a ‘rate for the job’ – subcontractors can undercut their competitors by tendering with wage rates below the industry standard. This practice was rife at the QCH site. Before the strike, the rate for similar jobs varied in some cases by up to $10 an hour. While some of the subcontractors did well out of this, the largest beneficiaries were Abigroup and Lend Lease. Above the fray, like touts at a dog fight, this conglomerate stood to profit from a divided labour force – from workers competing as self-employed subbies, from workers looking for a start through small subcontractors or labour hire companies, each with its own conditions and rates of pay on offer.

Across the different classifications levels, trades and positions at the hospital site, however, the concept of common conditions, and the sense of common interests and common purpose, held strong. The issue came to a head after a gyprocking subcontractor went broke and Abigroup signed up a replacement on sub-standard rates. Work on the site stopped in protest on 6 August. No more work would be done, the workers declared, until a union agreement with a subcontractors’ clause was conceded.

Usually, disputes in construction are over in days, the bosses preferring to settle quickly rather than incur the costs and penalties of long delays. But despite losing $300,000 a day, Abigroup refused to negotiate. They sought and were granted court orders declaring the strike unlawful and directing the workers to resume work. When the workers remained defiant, the Federal Magistrates Court granted Abigroup’s application for injunctions preventing two unions and certain organisers and delegates from assisting the industrial action, banning them from even attending the protest gatherings outside the site. The workers then invited seafarer and former BLF organiser Bob Carnegie to help organise the daily protest. On 7 September, he, too, was banned from further involvement. While union delegates and organisers obeyed the court, Bob continued to attend the protest each morning.

Early in the dispute, some other sites in Brisbane stopped work for short periods in solidarity. Later, workers on Baulderstone sites across Australia downed tools. Baulderstone is another Lend Lease subsidiary. These actions added to the pressure on Abigroup to negotiate. But the key to the strike’s success and its most outstanding feature was the resolve and unity of the QCH workers themselves. As one worker put it bluntly when asked in week seven about the hardship of such a long struggle, ‘Well, that’s just the way it is.’ His was a common outlook. Having taken a stand together, these men and women were resolved to see it through to the end.

Abigroup underestimated this commitment. Despite weeks of company intimidation, court action against their leaders and financial deprivation, the workers couldn’t be broken. On 2 October they marched back in as one. Victorious! Their victory is in fact our victory, a blow for all of us against a system that wants to consign working people to a never-ending economic race to the bottom. The QCH workers showed an alternative is possible.

But they still need our support. Despite a stream of financial and in-kind assistance from around the country and overseas during the strike, many of the workers continue to face financial hardship as a result of almost eight weeks without wages. And since the dispute ended, Bob Carnegie has, on the instigation of Abigroup, been charged with contempt of court for his leadership role. So a battle has been won but the struggle goes on. Show your support and join in the victory celebrations at the ‘Voices for Victory’ benefit concert on 27 October.

Candombe Mulato

Wide Awake – the rise of union solidarity

In early 1998, around Australia, thousands of workers massed in solidarity with the Maritime Union of Australia. “MUA HERE TO STAY,’’ they chanted. Many workers and socialists were hoping that the tide had turned, that unionism was returning as a growing force in the Australian political landscape. The pickets, the rallies and the overwhelming sense of solidarity contributed to the determined resistance and the euphoria surrounding the victory in the High Court which permitted the wharfies, who had been sacked by the stevedoring company, Patricks, to return to work.

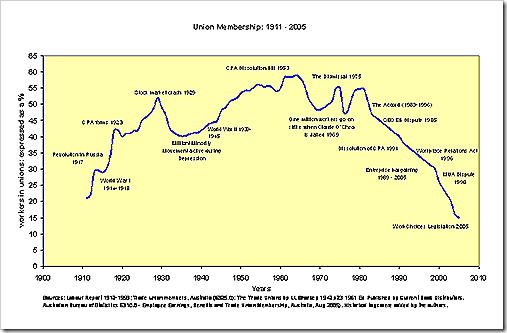

In the following years, it became clear that the optimism of the period did not translate into a resurgence in union membership. The membership levels of unions continued to fall, particularly in the private sector. In 1960 union membership was about 60% of all workers, by 1998 it had fallen to approximately 30% and in 2005 it fell below 20%. The graph overleaf illustrates the broad trajectory of trade union membership levels in Australia throughout the 20th century and into the 21st century.[1]

From the beginning of the First World War to the beginning of the Second World War the number of trade union members nearly doubled, in spite of the difficulties faced during the Depression. After the Second World War the efforts of the union militants were rewarded with strong union participation by the working class in the 1950s and 1960s. This period saw unions at their strongest at the May Day, Eight Hour Day or Labour Day celebrations (depending on which State you were in). Rank upon rank of union members marching proudly down streets in towns and cities were clapped along by crowds of onlookers, family, friends, and other supporters. None of this would probably have been possible without the hard organising work done in the 1930s by the communists in the militant minority movement, the unemployed workers’ unions and others.

“Riotous Demonstration in City Streets”

So began the news story in the Sydney Morning Herald reporting the 1927 timber workers’ struggle in its usual sensational anti-worker style.[2]

The report continued with time-worn stereotypes of worker and unionist:

Ballot Papers and Effigy Burned

Police Draw Batons

Riotous scenes unprecedented in Australian trade union history were witnessed in the city last night when the striking timber workers, led by the Communists, held a street procession and demonstrated as a protest against the Lukin award.[3]

In defiance of warnings by the Federal authorities and the police, ballot papers were collected from the strikers, placed in a large canvas bag, saturated with kerosene, and publicly burned in a kerosene tin outside the Trades Hall. Later an effigy of Mr. Justice Lukin was burned by the Communist section of a crowd in Hyde Park although an undertaking had been given to the Commissioner of Police by Mr. J. S. Garden that this would not be done.

Traffic was blocked and standing room was scarcely possible. As the ballot papers, saturated with kerosene, burned brightly, the ‘Red Flag’ and ‘Solidarity Forever’ were sung. Derisive jeers for Judge Lukin followed and then orders were shouted from a Trades Hall balcony for the men to take their allotted places in the procession.

Posters displayed were ‘Lukin award means – heads the bosses win, tails the workers lose.’ ‘Result of the secret ballot can have no effect on the award; award must continue whatever the result of the ballot may; therefore, this ballot is the best joke of the year.’

Notwithstanding the sensational reporting, the story shows that the approach to advancing workers interests was clearly based in the militant collective action of the workers themselves. Seventy years later, events leading up to the 1998 MUA dispute showed glimpses of this strategy.

In the ongoing dispute with Patricks Stevedores, CEO Chris Corrigan sacked 55 wharfies in Sydney in 1994. The wharfies took their redundancy payment cheques to the Waterside Workers Federation offices to be put in a plastic bag until the dispute was over.[4]After the men were re-instated the then MUA national secretary, John Coombs, took the cheques and dumped them on Corrigan’s desk.

Solidarity from the other unions and the community in the 1998 MUA dispute was also a flashback to the past, mirroring support received by the Timber Workers of 1929. However, more often than not, current trade union strategy is subsumed in legal manoeuvring, not the defiant burning of ballot papers by strikers.

The right to organise

Unions now struggle for relevance in Australian social and industrial worlds, yet they are needed just as much as at any time in the past 120 years. In the capitalist system, workers engaged in the selling of their labour remain in fundamental opposition to the employers who benefit from their exploitation of workers. It is also still true that workers are best served by unions that organise to represent them as a collective whole.

While the opponents of unions have ridden high since the election of the Howard Government, it may be comforting to think that it was easier to combat these opponents in the past. However, this is not the case. Over forty years ago, Jack McPhillips, former assistant national secretary of the Iron Workers Union, said:

“Workers won the right to organise, form unions and act together to defend and improve wages and working conditions only after bitter struggle against the combined forces of employers and governments.

Moreover the media has stood against workers and their unions since their very beginnings:

“The trade unions are, we have no doubts, the most dangerous institutions that were ever permitted to take root under the shelter of the law in any country’ (The Morning Post, 29 March 1834).”

Unions are now accused in the media of pursuing sectional interests against the common good. For instance, while the Maritime Union of Australia (MUA) and its predecessors, the Seamen’s Union and the Waterside Workers Federation, had struggled hard to win good wages and conditions for their members in the 1950s the union continued to be vilified in the mass media as a corrupt organisation rorting the system on behalf of a privileged group of workers. So effective was this propagandising by the media that many within the working class to this day believe that wharfies had it easy and that the system needed reform.

The mass media took up the Federal Government’s portrayal of the 1998 MUA dispute as a dispute about wharf productivity. However the working class movement understood instinctively that the allegations of low container loading rates were an assault on the union’s right to collectively organise.

The dispute showed workers’ employment contracts were not legally enforceable and only had weight through the collective strength of waterside workers’ organisation. Corrigan’s use of labour hire companies to lock out the wharfies and rob them of their entitlements was only possible because there had been a serious decline in the industrial power of workers and unions since the early 1970s.

The 1996-2007 Federal Government continued the assault on the organised working class by successive governments, undertaking to get rid of collective bargaining and the right to strike. One of the strategies was the introduction of secret ballots, designed to undermine decision making. Secret ballots are part of the arsenal of employers in isolating workers, creating fear and eroding the solidarity between workers, and so diminishing their collective strength.

During its history, the union movement overcame attacks such as these and established certain minimum union rights. These rights became an integral part of the struggles to defend and improve living standards.

Jack McPhillips listed trade union democratic rights as:

1. The right to form unions and to have them recognised by law.

2. The right of unions to exist independent of government control or interference from employers and other outside forces; and the right of union members to control their own organisations.

3. The right to bargain, to enter into agreements or contracts concerning wages and conditions.

4. The right to have these enforceable by law as minimum standards, i.e. the right to legalised wages.

5. The right to carry out activity for political aims.

6. The right of workers to strike and otherwise to restrict the use of their labour; and to be supported by other workers.

7. The right to elect representatives of a union’s members on a job to act on behalf of the union and the members, free from victimisation by employers.

8. The right to hold meetings on the job.

9. The right of trade union representatives to enter an employer’s premises and to inspect his time and wages records, in order to enrol members, discuss union business with members, police and enforce the operation of awards, agreements and industrial legislation.[5]

McPhillips was a communist worker and union leader. Communists no longer lead unions. Instead a weakened union leadership fights to maintain arbitration and conciliation courts they once attacked for restraining rather than supporting trade union rights.

After World War II, in a climate of shortages, the working class was in the ascendancy. But the arbitration and conciliation system was impeding the progress of workers by forcing unions to bend to the combined power of the state and the individual employer.

Employers standing alone feared the might of union solidarity.

Conciliation and arbitration courts sought to limit workers’ power by appealing to workers’ national consciousness to subsume their rights to a common good. In reality this was just a smoke screen to prevent growth in wages and workers’ power. This was well recognised by communist union officials who sought not to be fettered by nationalism and stood for workers’ rights first and foremost.

Unions like the wharfies that organised ‘on the factory floor’ held their own against employer and courts through the post war period up till the mid 1970s. This is reflected in the graph showing union membership in Australia. But a new challenge was to confront workers, the era of economic rationalism.

This program was compiled by Ian Curr from a variety of sources. It was first broadcast on 4ZZZ fm 102.1 on 19 October 2010 at 12 noon on the Paradigm Shift. Thanks to aritists and friends Lachlan & Sue for allowing me to use their songs by Jumping Fences in this podcast. Thanks to LeftPress for producing the book After the Waterfront – the workers are quiet (Wide awake comes from Chapter 1 of that book).

[1] 1301.0 – ABS Year Book Australia, 2003

[2] Thornton, Ernie. Stronger Trades Unions—Opponents Answered. The facts of Amalgamations, Secret Ballots, Balance Sheets.

[3] On 13 January 1929, Arbitration Court Judge Lukin made a new award for timberworkers, which increased hours to a standard 48 for all timberworkers, cut wages 10% (despite a 5.7% increase in the cost of living), and increased the employment of youth at lower wages (likely to displace 2,000 men). This was definitely one of the worst awards in Australian history. From the Plague to Reith By Eric Petersen in Marxist Interventions http://www.anu.edu.au/polsci/marx/interventions/law.htm

[4] Coombs told this story at the first stop work meeting in Brisbane just prior to the April 7 mass sackings. He described how the wharfies in Sydney had dealt with previous attempts by Patricks to sack them. He pointed out that none of his officials had asked them to surrender the redundancy cheques. They knew that redundancy on Patrick’s terms spelt the end of the union. This will be dealt with in more detail later.

[5] McPhillips, Jack. Penal Powers Cost Unionists £1,000,000! (Sydney: Current Book Distributors 1963 at p13).

Support the QCH Workers Celebrate their Historic Victory!

Where: Serbian Hall, 243-7 Vulture St, South Brisbane (opposite South Bank Railway station)

Time: 7.00 pm

When: Saturday 27 October,

Admission: $10.00 waged, $8.00 unwaged

BBQ and Bar from 5.30pm

Featuring a Fine Musical Line-up —

Support the QCH Workers Celebrate their Historic Victory!

Combined Unions Choir

The Combined Unions Choir raises awareness of the struggles and achievements of working people through music.

Mark Cryle and the Redeemers

“Mark Cryle is one of Australia’s finest storytellers” Country Update

3 Miles from Texas

Phil Monsour

Phil Monsour is an “Australian troubadour who sings songs of hope, humanity, invasion and occupations.”

Jumping Fences

Jumping Fences is an enduring musical partnership between Sue Monk and Lachlan Hurse. Jumping Fences plays inspiring songs for working people.

Defend the Right to Organise!

Trade Union Defence Committee wishes to thank these artists for their generous support in giving their creative talents and energy to this important struggle.

Contact: Ian Curr iancurr@bigpond.com mob +61 0407 687 016

Authorised by Trade Union Defence Committee PO Box 5093 West End 4101

[soundcloud url="http://api.soundcloud.com/playlists/2641987" height="200" iframe="true" /]